Since Russ & Daughters opened in Manhattan in 1914, the family-run store has weathered the Spanish flu, two world wars, recessions and the Great Depression. With the new coronavirus pandemic sweeping the country, the current generation, Niki Russ Federman and Josh Russ Tupper, is doing what the family has always done: deliver bagels and cream cheese, lox and herring to people craving the emotional sustenance that the traditional Jewish favorites bring.

At Katz’s Delicatessen, Jake Dell begins his mornings making matzoh balls to keep up with the spike in orders for matzoh ball soup as his customers seek comfort in uncertain times. The deli whose slogan became “Send a Salami to Your Boy in the Army” during World War II is now delivering matzoh ball soup to seniors, low-income residents and New York City health care workers.

“There’s something very reassuring about it, something very normal about it,” Dell said.

The owners of the two Lower East Side landmark institutions are among the chefs and scholars, historians and cookbook authors who are featured in the newest online course to be offered by YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. “A Seat at the Table: A Journey into Jewish Food” will be launched on May 1 and because of the coronavirus pandemic it will be free.

Two years in the making, the course provides a history of Ashkenazi food, or the cuisine of Eastern Europe, looking at it from its origin in religion and texts to its spread through diasporas around the world. The lectures use food as a way to teach history, with one on borscht, for example, exploring how borders and concepts of national identity change, and others looking at differences among traditions of the Ashkenazi, the Sephardic Jews of Spain and Portugal and the Mizrahi Jews of the Middle East and Central Asia.

Darra Goldstein, a retired Russian professor who taught at Williams College and a cookbook author, leads the course with more than 20 chefs, writers, culinary historians and others. There are cooking demonstrations by Liz Alpern and Jeffrey Yoskowitz of The Gefilteria in New York City, virtual visits to Russ & Daughters and Katz’s Delicatessen and short video lectures by Ilan Stavans, the Mexican-American essayist who writes on American, Hispanic and Jewish cultures. Michael Twitty, known for exploring the legacy of Africa in American Southern cooking and his blending together of kosher and soul food, is also among those participating.

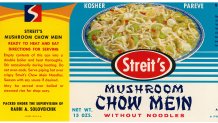

Goldstein conceived of different mini-lectures and thought of who should present them. She talks about cookbooks as social documents, rich in what they can say about how society changes, and about how corporations advertised products to Jewish households. Objects from the YIVO archives help to tell the story: packaging for Streit’s kosher chow mein from the 1950s, a pushcart permit issued to Israel Bloom of New York City’s Delancey Street in 1923, and a photograph of women and children in Bialystok, Poland, in 1932, carrying pots for cholent, a slow-cooked stew that conforms with a prohibition against work on the Sabbath.

“The roots of Ashkenazi cooking lie in if not quite poverty, then certainly not in abundance for most people,” she said. “Obviously there were wealthy people who could eat more lavishly, but it’s a lot of very basic foods that would be prepared by putting more than one ingredient together, so that what you end up with is a really delicious dish that is more than the sum of its parts. And so I think that that’s something that we can learn to do in our quarantine times.”

Goldstein herself had gotten black radishes from a friend, was planning to grate them and combine them with onions, salt, and schmaltz or rendered chicken fat, and then refrigerate the mixture for four or five days. The result is a spread, one that her father really loved and would put on black bread, she said.

“I think it’s about trying to find a way to make something really special out of what might be very basic,” she said.

The Scene

“A Seat at the Table” is made up of seven units, which will come out in installments once a week and which include about 100 videos. As of last week, about 1,000 people had registered for the course and more than 2,000 for all of YIVO’s online classes, which have been free since mid-March. The food course was to have cost $55 for YIVO members and $60 for non-members.

One idea is to reclaim the cuisine from a stereotype of heavy, heartburn-inducing meals, said Ben Kaplan, YIVO's director of education. What’s been lost is its original character, its roots in fresh vegetables and fruits tied to the land of Eastern Europe, he said.

“It actually can be eaten in a way that’s healthy, it can be eaten in a way that connects people to local farms,” he said.

That is what motivated Liz Alpern and Jeffrey Yoskowitz to open The Gefilteria. They shared a passion for Ashkenazi food even as it was dismissed as bland, boring and flavorless, Alpern said.

“We took gefilte fish out of the jar,” she said, because for them nothing better symbolized how bad things had gotten. They turned their attention to making a high-quality version before moving on to all the other foods of the Ashkenazi canon — pickles, chicken soup, borscht and handmade matzoh, she said.

A lot of Jewish food was victim to mid-century industrialization and they set out to make it relevant and hip and sexy, Yoskowitz said, with fresh flavors and local and thoughtfully sourced ingredients. They traveled to Eastern Europe, read old memoirs and cookbooks, saw the resourcefulness that had been such an element of Jewish cooking before it was lost to the abundance in America and explored fermented vegetables, sour pickles and sauerkraut brine that is probiotic, he said.

“That was a huge part of the wisdom of Jewish life, preserving food from times of abundance to times of scarcity and not just preserving them but actually improving their nutritional quality," Yoskowitz said.

Russ & Daughters has seen a surge in orders from people stocking up not only for themselves but also sending care packages across the country of bagels and lox and babkas and latkes, said Niki Russ Federman.

"All the things that we bake and are known for are stand-ins for people to be able to say, 'I can’t be with you right now but I’m sending you love,'" she said.

Like Katz's Delicatessen, the store is also delivering to the community, to hospitals, nursing homes, churches and community centers.

"So every week, we're feeding a couple of thousand people on the front lines," she said.

Kaplan said the course does not shy away from poverty or how people ate in the displaced persons camps after World War II.

“You see how resilient and resourceful and creative people can be and those to me feel like very relevant themes for this time,” he said.