Even as scientists push for an extension to the GEDI Mission, which they say is providing vital insights in coping with climate change, NASA has plans to jettison the project from the International Space Station and let it to burn up in the earth’s atmosphere in the coming year.

GEDI, short for Global Ecosystem Dynamics Investigation, uses specially designed lasers, known as LIDAR technology, to map the earth’s rainforests and vegetation. Since 2019, GEDI has built and continues to build a detailed database of carbon contained in the earth’s forests, which scientists can use to make decisions on how to cope with greenhouse gas emissions. Despite pressure from the scientific community, NASA said a new Defense Department experiment, known as STP-H9, will replace GEDI as scheduled in January 2023.

(Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center)

From aboard the space station, GEDI, a refrigerator-sized box, takes snapshots of 25-meter circles, or “footprints,” as it orbits the earth. As it circles the planet every 90 minutes, the sensor creates a more accurate and complete view of the earth’s vegetation than was previously possible, capturing 3-dimensional samples of the earth’s forests in each of billions of 25-meter footprints. These can be used to create maps that show the height of the trees and structure of their canopies. By correlating with other information, such as the type of vegetation in a particular area, scientists are able to calculate how much carbon is stored in a forest, and how much carbon dioxide (CO2) a forest is able to absorb from the atmosphere.

“One of the biggest unknowns in the greenhouse gas emissions is…how much are plants, trees, forests going to be able to take up in CO2 to get us out of the mess we're in?” said Dr. Rebecca Shaw, Chief Scientist of the World Wildlife Fund. With a stated mission of protecting the future of nature, WWF placed high value on the tools for fighting climate change.

“From a science perspective, it is a no brainer to keep GEDI up,” said Dr. Shaw, “Particularly given that we've just set some major global goals to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and that the detection of the information we're getting from the GEDI mission is critical to those decisions and those actions.”

Over the past five years, the U.S. produced an average of about 10.6 trillion pounds of carbon dioxide per year, mostly by burning fossil fuels, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 2020 was an outlier year due to the pandemic.

Get a weekly recap of the latest San Francisco Bay Area housing news. Sign up for NBC Bay Area’s Housing Deconstructed newsletter.

According to the European Environment Agency, a single, growing, mature tree can absorb about 48 pounds of CO2 in a year. Based on the U.S. Forest Service Inventory, the trees across the entire United States can absorb about 14% of the nation’s CO2 emissions each year. But forest analysts said that number is going down as trees are lost to fire, development and insect infestation.

Dr. Ralph Dubayah, lead scientist on the GEDI mission, points out that forest inventories are plagued with inaccuracy because smaller stands of trees are often missed in the count. Walking around in a wooded area in Menlo Park, Dr. Dubayah said, “This is not considered a forest and so it's not in anybody's spreadsheet.”

Local

In a study with the U.S. Forest Service in Maryland, Dubayah found that past estimates can be off by as much as 30%. One of the aims of the GEDI mission is to capture the missing data.

Dubayah and his team have been trying to launch a satellite like GEDI into space for more than 20 years. Since 1997, they have repeatedly hit dead ends: technology failed, proposals were rejected, projects were started and then cancelled by NASA.

Finally, on December 5, 2018, Dubayah and his team watched at Cape Canaveral as the SpaceX rocket launched their $100 million project.

“Next to my children being born, watching that Space X launch go up into space was probably one of the greatest moments of my life,” said Dr. Dubayah.

But as Dr. Dubayah and his team analyzed the data coming from the GEDI satellite, they were sure something was wrong. “We just kept going over the same area every four days.”

The team eventually discovered the problem. The orbit of the International Space Station had been changed by about 11 miles. It took over a year to get the International Space Station to agree to change back to the optimal orbit, and even then, says Dr. Dubayah, there have been variations that disrupted the data. Because of those delays, NASA and the International Space Station agreed to extended the GEDI mission, but many scientists, pointing to the value of the data, have been asking for yet another extension.

NASA officials declined a request for an interview, but in a written statement said GEDI had “already been extended” once to “allow for additional data collection” and is now “scheduled to be replaced by a new experiment.

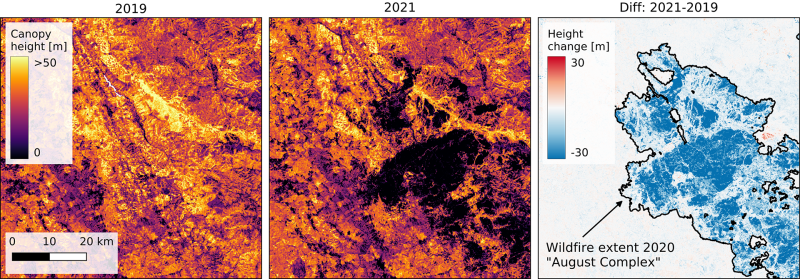

Some scientists told NBC Bay Area they find the GEDI data so useful, they would like to see the mission extended indefinitely. Nico Lang, a PhD candidate at ETH Zurich, (Albert Einstein’s alma mater), is using GEDI and other satellite data to map the impact of fire on California forests. His team created a map of the area that burned in the August Complex Fire, which burned more than one million acres in six Northern California counties. Lang’s map aligns closely with the Forest Service map of the fire. “We see actually the biggest difference happens in these areas where the fire that was going on,” said Lang.

In the coming months, Lang says he and his team may be able to arrive at a precise number for how much of the forest was lost, and how much Co2 was released in the fire.

“You can quantify actually what's an impact of such a fire on the climate at some point,” said Lang, who hopes GEDI data will continue to be available as a guidepost for climate research.

“An extension of that would be very helpful,” said Lang, “as long as possible.”

Sean Healey, research ecologist for the U.S. Forest Service, agreed.

“GEDI represents detailed forest height data that has never before been available in such quantity and with such global consistency,” he said. “The Forest Service and its stakeholders are just scratching the surface of the insights this dataset provides.”

Private industry is also using the data stream from GEDI. “I think that in one or two decades, it’s almost going to be impossible to operate a profitable business if you are not taking responsibility for the climate,” said Diego Saez-Gil, co-founder of a Silicon Valley startup called Pachama. Born in Argentina, Saez-Gil witnessed firsthand the impact of agriculture and logging on the Amazon Rainforest. “Unfortunately, it’s happening all over the world,” said Saez-Gil. He was looking for a way to make it profitable to save a forest, so he started a company called, Pachama - a shortened version of “Pachamama,” the “Mother Earth” goddess to Andean indigenous people. Saez-Gil offers corporations a way to offset their pollution by paying to preserve forests and plant trees.

“We would present you with a portfolio of forest projects ranging from Alaska to Indonesia and everything in between,” said Saez-Gil. Similar ventures have struggled in the past because it wasn’t possible to provide an accurate assessment of the growth of a forest. Saez-Gil’s company relies on GEDI data for that accountability. The company website advertises: “Carbon Credits You Can Trust.”

House Representative Zoe Lofgren, who sits on the U.S. House Science, Space and Technology Committee, which oversees NASA, said in a statement, "NASA missions, like GEDI, that are providing insightful data for scientists are worthwhile investments and these programs should be prioritized, not phased out.”

In a follow-up statement, NASA officials said, “If there was space available on the space station, NASA would consider a mission extension.”

“We should not be destroying one of the best tools that we have,” said Dr. Ralph Dubayah. “This represents really one of the easiest ways that we can manage atmospheric CO2. We can’t take refrigerators and cool down the poles so that the ice sheets don’t melt, but we can all go into our backyards and plant trees. We can preserve the forests that we have.”