More than three years after a civil grand jury blasted the San Jose Fire Department for the lack of women wearing the uniform, advocates pushing for better representation in the fire service say the agency has failed to make meaningful progress.

Today, women make up fewer than 4% of San Jose firefighters and the department has been rocked by a wave of scandals since the grand jury’s findings. The heart of the issue, critics say, is a pervasive frat house culture and a widespread stigma that women can’t perform at the same level as men, despite being held to the same professional and fitness standards.

“If there’s no accountability, it just gets worse,” said Orange County Fire Captain Lauren Andrade, who co-founded the non-profit advocacy group Equity on Fire. “And that’s basically what happened at San Jose.”

Just this April, San Jose Fire Captain Spencer Parker resigned after being arrested in a Sacramento Sheriff’s Office child sex crime sting. He now faces multiple charges for attempted lewd acts with a 13-year-old girl. San Jose Mayor Matt Mahan said he was “sickened” by the allegations.

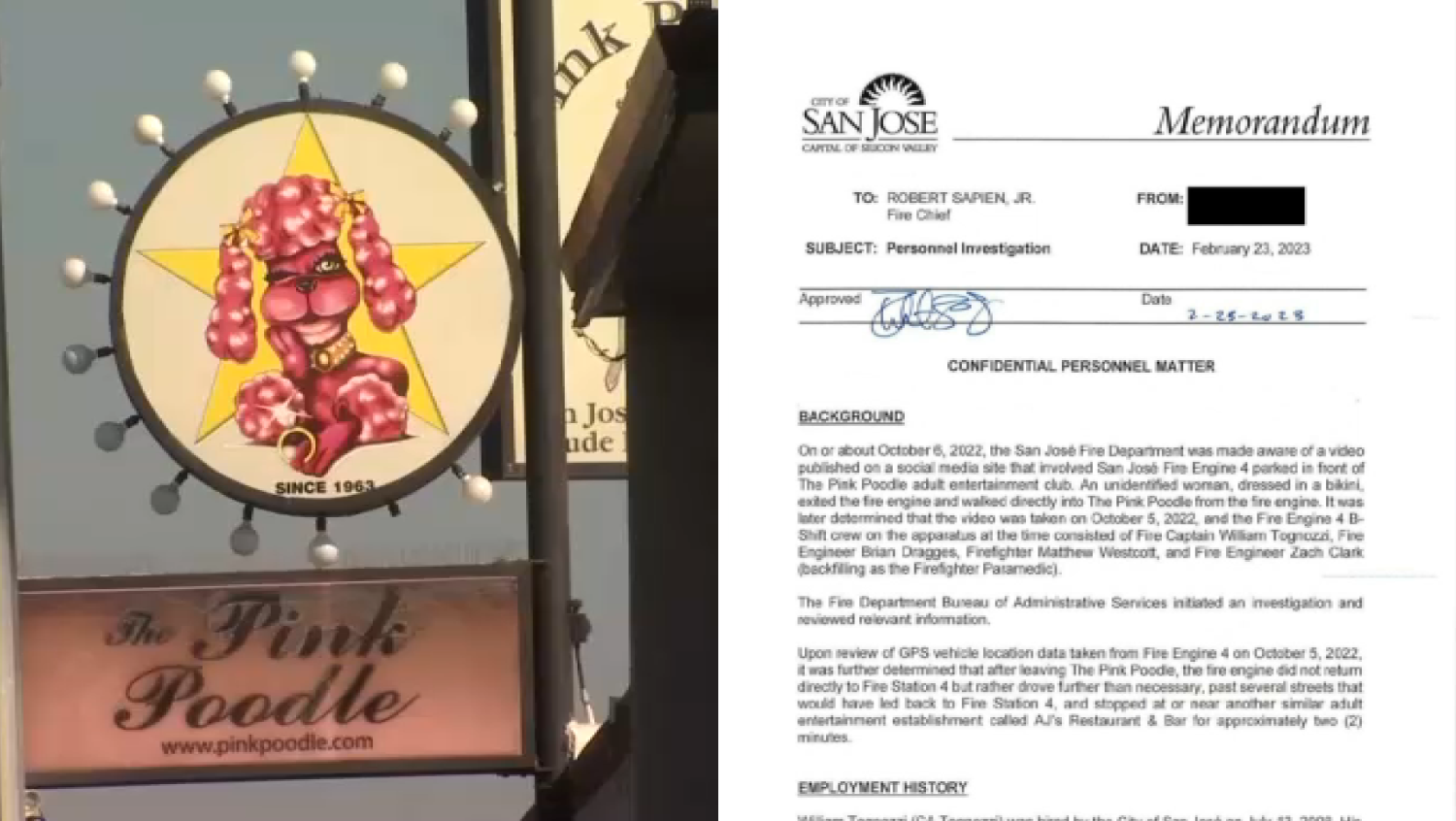

Before that, there was a 2023 lawsuit alleging sexual assault and harassment by men in the department, and the infamous Pink Poodle incident from 2022, where a bystander’s cell phone camera captured a dancer walking out of a San Jose fire truck wearing a bikini and high heels before strolling into the adult entertainment club.

“The Pink Poodle incident, that doesn’t seem out of the ordinary for San Jose,” said former San Jose firefighter Cassie Loessberg.

As the city grappled with the fallout from the Pink Poodle incident, Loessberg was grappling with something much darker from her own time as a San Jose firefighter. The former college athlete and Marine Corps veteran filed a still-active lawsuit against the department in 2023, alleging she was sexually assaulted by a male colleague and harassed by others.

“He came around the truck and he stuck his hands in my pants and pushed me up against the apparatus door,” Loessberg said, describing her alleged sexual assault. “He was a very large man and a supervisor at that time, a higher-ranking firefighter, so I felt frozen. I felt scared and I felt very violated, and that was the start of my career.”

Loessberg’s nightmare in the department didn’t end there, she said. Between 2017 and 2021, her lawsuit alleges she was the target of “unrelenting sexual harassment” by two other male firefighters and subjected to anti-Semitic and racist remarks by another male in the department who “drew swastikas on the white board in the kitchen at Station 3” and repeatedly used the “N-word."

Get a weekly recap of the latest San Francisco Bay Area housing news. Sign up for NBC Bay Area’s Housing Deconstructed newsletter.

“When another firefighter gets your number off of staffing and asks you if you’re single, or sends you pornographic photos on Snapchat, or invites you over to their home when their wife isn’t there,” Loessberg said. “That creates fear. That creates a lack of safety and that directly affects performance.”

Despite graduating first in her class at the fire academy, Loessberg said male colleagues routinely questioned her ability to do the job or complained about having to work with a woman.

"There's absolutely a stigma," Loessberg said. "That's coming from the culture, a deeply embedded, fractured culture. It's really interesting to have that when you have all of us women that have been hired and went through the same exact academy and completed it, and still endure that sort of discrimination."

San Jose Fire Chief Robert Sapien said he couldn’t comment on any pending litigation, but said he took anything that damaged the reputation of the department, such as the Pink Poodle affair, seriously.

“Certainly, public image and perception of the organization is critical to our recruitment process,” Sapien said. “It’s critical to the confidence that our community has in our organization.”

At the same time, Loessberg said she was facing chronic harassment on the job; the Santa Clara County Civil Grand Jury released a report titled “Why Aren’t There More Female Firefighters in Santa Clara County?”

The Grand Jury’s 2020 report found that only 16 of the department’s 665 firefighters were women, down from 35 a decade earlier. At just 2%, It was the lowest percentage of female firefighters among the South Bay departments studied by the Grand Jury.

“So, we’re actually going backwards,” Andrade said. “With a woman firefighter, she comes in and she’s looked at immediately as the weakest link.”

The Grand Jury blamed the low numbers on a lackluster effort to recruit women, poor fitting uniforms and gear for female firefighters, and a work environment that makes it “challenging for women to report discrimination and harassment,” which is something Loessberg said she can identify with.

“That if I speak out against something like this, that I will be shunned, that I will be bullied, that I will be discriminated against even more,” Loessberg said.

The report also found some San Jose fire stations lacked separate bathrooms, dorms and locker rooms for women, which remains the case today.

Sapien said the department has taken steps to address the Grand Jury’s findings, such as installing dividers in shared sleeping areas, pumping money into recruitment, and working with vendors to provide more custom fitting options for uniforms and gear. He also touted the department’s women’s boot camp, which introduces potential recruits to the fire service.

“An immediate response to the report was to address the facilities, the uniforms and personal protective equipment,” Sapien said.

While the department has hired more women since the Grand Jury report, there are still only 24 women in the department, fewer than 4% of its firefighters. By comparison, women make up 15% of the San Francisco Fire Department, the highest in the country.

Just four out of 162 San Jose fire captains are women, and there’s only one woman among the department’s 24 battalion chiefs.

The underrepresentation of women in the fire service isn’t confined to San Jose. According to 2022 data from the National Fire Protection Association, about 9% of all firefighters in the United States are women. But the number dips to under 5% when volunteer firefighters are removed from the equation.

Sapien said recruitment efforts have become more difficult over the years, pointing to increasingly stricter entry-level hiring standards in his department, which shrinks the pool of eligible candidates that’s already thin on women.

Even so, Sapien said “we need to do much better.”

“Our number was up in the 40’s,” Sapien said. “We’ve had attrition since then. In those decades between then and now, we didn’t do a great job in recruiting women. And I don’t think that’s necessarily because the department was unwilling to do so. I think we just haven’t overcome the challenges that are present in that process.”

Despite the new efforts listed by Sapien, NBC Bay Area’s Investigative Unit confirmed the department never followed through on some of the assurances it made in response to the Grand Jury’s findings back in 2021.

After the Grand Jury found there were four fire stations with no separate locker rooms for women, 14 stations with no separate dorms, and four stations with no separate restrooms with showers for women, the department said it would gather employee concerns and develop a work plan that would be submitted to Chief Sapien by May 2021, and later to the city manager.

The department made similar promises that it would create reports by May 2021 addressing “challenges for female firefighters” in the department, as well as the findings on uniforms and gear.

But NBC Bay Area confirmed those reports were never completed, though Sapien said the department did use a stakeholder committee and other department staff to evaluate those issues and provide recommendations to the Chief.

“We thought it would bring change,” former San Jose Fire Department Battalion Chief Patricia Tapia said of the Grand Jury’s findings. “[Other agencies] took it as an opportunity to point the lens at themselves and reflect on where they were and what kind of work they were doing and where they were falling short. And sadly, my department didn’t do that.”

Tapia was one of the first women to wear the uniform for the city when she joined up back in the 1980s, later rising to the rank of battalion chief. But Tapia said her career in the department was marred by sexism, harassment, and retaliation.

Tapia settled her first gender discrimination lawsuit in 2012 after she and another fire captain were passed over for open battalion chief positions.

“She came out number one, I came out number eight [on the test],” Tapia said. There were nine positions. They skipped us both. You’ve performed the way they want you to and checked all the boxes, and for no reason, they say, ‘no.’”

In 2017, Tapia won a second lawsuit against the city, also alleging gender discrimination, as well as harassment and retaliation when she spoke up about it. A jury awarded her $800,000 and she left the department the following year.

“We continue to create a culture where behavior that wouldn’t be acceptable in a normal workplace is acceptable in a firehouse,” Tapia said.

Despite their own experiences in the department, Tapia and Loessberg say young girls and women should still chase their dreams of becoming firefighters.

“You chase your dream, no matter what the cost,” Tapia said. “Because there’s a place for us in the fire service. There is a place for women in the fire service.”

They just hope the culture will be different by the time they get there.

“There is a culture that deserves to be looked at and deserves to have accountability,” Loessberg said. “And that accountability will create change.”