- The Covid recession, and the extreme inequality it wrought, will be among 2020's legacies.

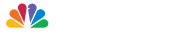

- Rich, White and college-educated Americans saw jobs recover quickly, and their wealth balloon as the stock market and housing prices reached new highs.

- Racial minorities, low earners, women and those without a college degree were more likely to be unemployed and fall into poverty.

The legacy of 2020 will endure in America's collective memory for many reasons: a deadly pandemic, a vicious presidential election.

It also brought the most severe recession in almost a century, which hurtled millions into poverty and joblessness and created burgeoning inequality.

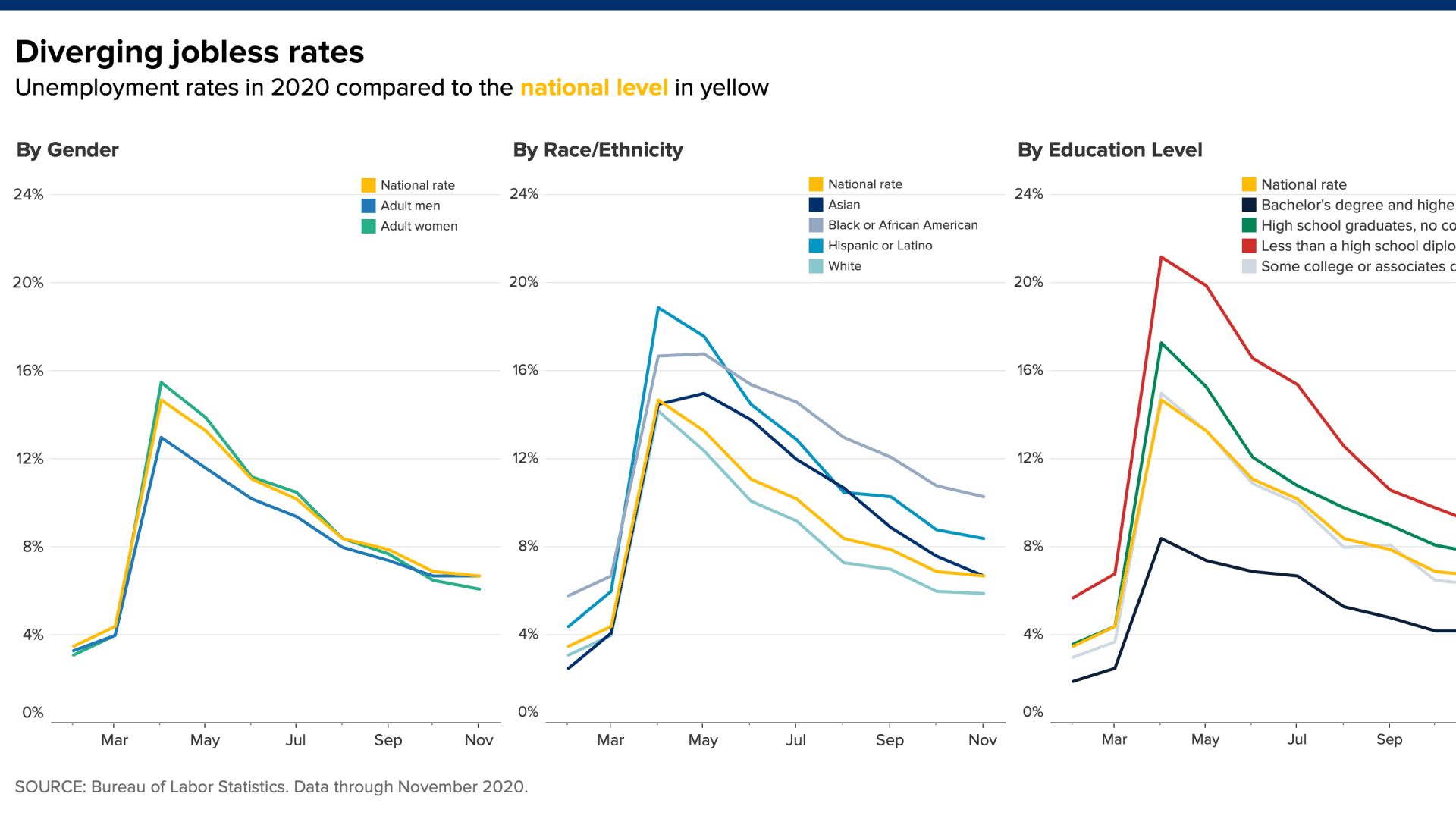

That financial pain has been concentrated among certain groups, like racial minorities, women, low earners, those without college degrees and workers in the service economy, like restaurant and retail jobs that require face-to-face contact. (These categories often overlap.)

'No pain at all'

To a certain extent, these dynamics play out in all downturns. But the coronavirus-fueled economic shock has been singular in the way rich, White Americans rebounded from the depths of the crisis.

For many of them, the recession ended months ago. They quickly recovered lost jobs. Their wealth has never been higher, as stocks and home prices soared. Their disproportionate ownership of such assets means other groups shared little in their riches.

The result is a financial chasm between the have and the have-nots that emerged faster than prior downturns, according to economists.

Money Report

"The most marginalized groups always get hit the hardest," according to Wendy Edelberg, director of the Hamilton Project, an economic policy arm of the Brookings Institution.

"But what is so unusual is, for a lot of other groups, it's not that they're being hit less — it's that they're seeing no pain at all," she said. "And they're doing well."

Unequal recovery

The diverging experiences of those at the top and bottom have led many economists to identify the recovery as having a "K" shape.

But that unequal financial pain wasn't apparent in the early months of the pandemic recession.

Congress swiftly passed the CARES Act, a $2.2 trillion relief package, propping up household income with extra unemployment benefits and stimulus checks.

Nearly 40% of jobs had evaporated for the lowest earners by the height of the crisis, according to Harvard's Opportunity Insights project. But a $600 weekly boost to jobless benefits more than doubled household income for many of them.

The cash infusion helped lift millions out of poverty.

In June, there were almost 5 million fewer Americans among the ranks of the poor than at the start of the year, before the pandemic, according to data published by researchers at the University of Chicago, University of Notre Dame and Zhejiang University.

But inequality flourished as that aid ran dry.

Nearly 8 million people fell into poverty between June and November, the researchers found. Poverty grew in each successive month over that time, they found, increasing most for Blacks, children and those with a high school education or less.

Food insecurity has grown and more households report being behind on bills like rent, federal data shows.

More from Personal Finance:

Your second stimulus check may be delayed if you changed banks, moved

Workers left almost all of their vacation days on the table in 2020

New stimulus package makes it easier to qualify for food stamps

"This may not have been the most unequal recession, but it was clearly the most unequal recovery," said Olugbenga Ajilore, a senior economist at the Center for American Progress.

The new year may usher in buoyed household finances and reduced inequality. President Donald Trump has signed a $900 billion relief package into law, injecting families with extra jobless benefits until mid-March and $600-per-person stimulus checks.

Unemployment and jobs

Jobs among the lowest earners (those making less than $27,000 a year) were still down almost 20% from pre-pandemic levels by mid-November, according to Opportunity Insights. Extra unemployment aid expired months ago.

The unemployment rate for Blacks remains above 10% and is almost twice that of Whites, at 5.9%. Those without a high-school degree are also unemployed at a rate more than double those with a college degree.

The official jobless rate among women is also artificially low — women, more so than men, have left the labor force entirely due to childcare and other responsibilities, said Edelberg, a former chief economist at the Congressional Budget Office.

The rich prosper

Meanwhile, the highest earners (those making more than $60,000 a year) had fully recovered their job losses by the end of August, according to Opportunity Insights. By mid-November, they had about 1% more jobs than they did before the pandemic.

Richer Americans typically take a financial hit via their wealth holdings — stock and home prices, for example — rather than lost job income during recessions, economists said.

But that wealth has proved resilient in the Covid downturn.

"That's one of the things that makes this recession so unusual," Edelberg said. "For a lot of people, the crisis is over. It's invisible to them."

Stocks, homes

Stock prices (as measured by the S&P 500 index) plunged 34% by the market bottom on March 23 — the quickest decline of its kind in history. But they recovered at their fastest-ever clip, fully erasing losses by Aug. 21, less than five months later.

The S&P 500 has swelled by 67% from the market trough. The index was up more than 15% in 2020.

Home prices were also up almost 15% in November from the year prior, according to the National Association of Realtors. (The group measures median price, which is the one right in the middle of a range.)

Wealthy Americans are also spending about 5% less money than before the pandemic, while the lowest earners are spending about 3% more, according to Opportunity Insights. That suggests the wealthy may be boosting their savings, while others are unable to do so.

"Low earners] are living paycheck to paycheck, so any money they get they'll spend on bills, food," Ajilore said. "High-income [people] are maybe doing fewer leisure activities, so instead of spending it they're holding that money back."