- Former President Donald Trump said last week that the president "should at least have a say" in monetary policy. Sen. JD Vance of Ohio, Trump's running mate, backed that position.

- Interest rates are set by the Federal Reserve, which governs these decisions independently from the White House.

- Fed Chair Jerome Powell has maintained that politics will not play a role in the Fed's policy decisions.

When it comes to raising and lowering interest rates, Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump says the president should "at least have a say."

"They've gotten it wrong a lot," Trump said of the Federal Reserve's decision-making during a news conference Thursday at his Mar-a-Lago residence in Florida.

"In my case, I made a lot of money, I was very successful, and I think I have a better instinct than, in many cases, people that would be on the Federal Reserve or the chairman," Trump said.

Sen. JD Vance of Ohio, the Republican vice presidential nominee, echoed this opinion in a CNN interview that aired Sunday, saying that interest rate policy "should fundamentally be a political decision."

More from Personal Finance:

Harris: 'Building up' middle class is a defining goal

What Kamala Harris' latest financial disclosure reveals

The Fed sets the stage for a rate cut. What that means for you

Also over the weekend, Vice President Kamala Harris told reporters in Arizona that she "couldn't ... disagree more strongly" with Trump's suggestion that the president should have a voice in the central bank's monetary policy moves.

Money Report

"The Fed is an independent entity, and as president, I would never interfere in the decisions that the Fed makes," Harris said.

The president has no direct control over interest rates

Get a weekly recap of the latest San Francisco Bay Area housing news. Sign up for NBC Bay Area’s Housing Deconstructed newsletter.

As it stands, the president exerts no direct control over interest rates. The Federal Reserve sets interest rates, and it operates independently of the White House.

"While the Fed's day-to-day operations are intentionally removed from partisan political input to protect the central bank's integrity, the Fed and its conduct of monetary policy remain democratically accountable," said Brett House, economics professor at Columbia Business School.

Through the Federal Reserve Act, the legislative and executive branches of the government set the mandate of the Fed to promote maximum employment, keep prices stable and ensure moderate long-term interest rates, House explained.

"If a president wants to change this mandate, they always have the option to marshal support in Congress for an amendment of the act or new legislation," he added.

However, this is not the first time Trump has contended that the relationship between the executive branch and the Fed shouldn't necessarily work that way.

Last month, Trump said that if elected he would "bring interest rates way down."

Inflation and high interest rates are "destroying our country," the Republican presidential nominee said at the National Association of Black Journalists' annual convention in Chicago.

"I bring inflation way down, so people can buy bacon again, so people can buy a ham sandwich again, so that people can go to a restaurant and afford it," he said.

A rate cut is coming

Inflation has been a persistent problem since the Covid-19 pandemic, when price increases soared to their highest levels in more than 40 years. The Fed responded with a series of rate hikes to effectively pump the brakes on the economy in an effort to get inflation under control.

The federal funds rate, which sets overnight borrowing costs for banks but also influences consumer borrowing costs, is currently targeted in a range of 5.25% to 5.50%, the result of 11 rate increases between March 2022 and July 2023.

Now, recent economic data indicates that inflation is falling back toward the Fed's 2% target, paving the way for the central bank to lower its benchmark rate for the first time in years. The personal consumption expenditures price index — the Fed's preferred inflation gauge — showed a rise of 2.5% year over year in June.

Markets have fully priced in the likelihood of at least a quarter percentage point rate cut in September and a strong likelihood that the Fed will lower by a full percentage point by the end of the year.

Once the fed funds rate comes down, consumers may see their borrowing costs start to fall as well.

Trump has a contentious history with the Fed

Trump, who nominated Jerome Powell to head the nation's central bank in 2018, has been advocating for lower rates for years. The former president was a fierce critic of the Fed chief and his colleagues while he was in the Oval Office, skirting historical precedent by repeatedly and publicly berating the Fed's decision-making.

During that time, Trump complained that the central bank maintained a fed funds rate that was too high, making it harder for businesses and consumers to borrow and putting the U.S. at an economic disadvantage to countries with lower rates.

Ultimately, though, Trump's comments had no impact on the Fed's benchmark.

"Any chairman is going to remain loyal to the Fed's mandate over any browbeating from the White House," House said.

Now, however, Trump has cautioned against the Fed lowering rates shortly before the presidential election in November.

Trump told Bloomberg Businessweek in an interview in July that cutting rates in September, just weeks ahead of the election, is "something that [central bank officials] know they shouldn't be doing."

Earlier this year, the former president also told Fox Business that he would not reappoint Powell to lead the Fed.

"I think he's political," Trump said. "I think he's going to do something to probably help the Democrats, I think, if he lowers interest rates."

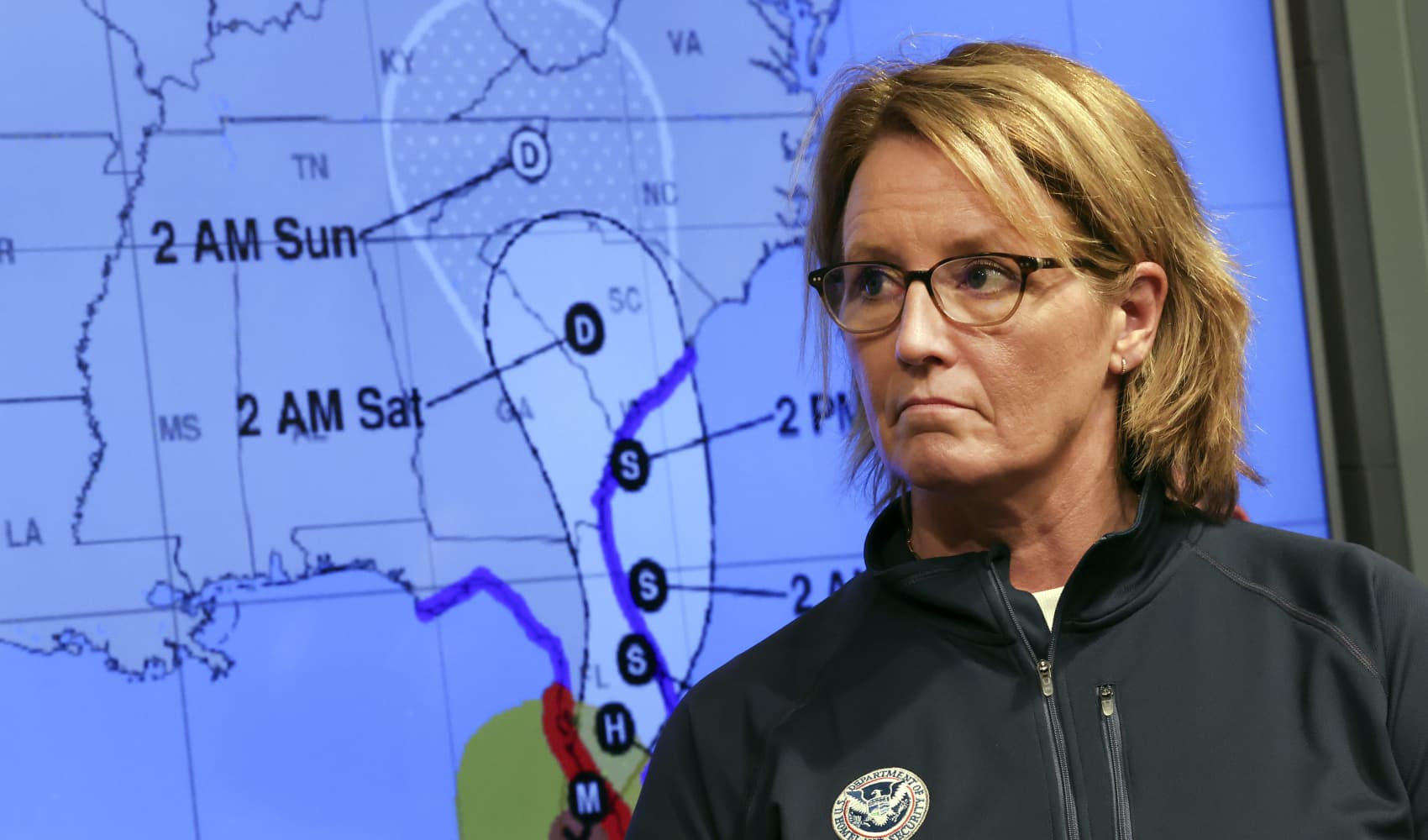

When asked about these comments during a press conference after the FOMC meeting last month, Powell underscored the Fed's singular focus on the economy.

"We don't change anything in our approach to address other factors like the political calendar," Powell said. "We never use our tools to support or oppose a political party, a politician or any political outcome."

According to Greg McBride, chief financial analyst at Bankrate.com, "the Fed's independence will remain paramount — regardless of who is president."

A 'consequential year' for monetary policy

The central bank is an independent agency that governs decisions about monetary policy without interference from the president or any branch of government. Therefore, it is theoretically free from political pressure.

Still, the stakes are high in 2024.

In January, Powell said at a press conference that this was going to be "a highly consequential year for, for the Fed and for monetary policy."

In the months that followed, signs of economic growth and cooling inflation laid the groundwork for a widely anticipated rate cut, which is welcome news for Americans struggling to keep up with sky-high interest charges.

After July's Federal Open Market Committee meeting, Powell said that central bankers would cut rates as soon as September, if the economic data supports it.

How the Fed adjusts policy during election years

In previous presidential election years, the Fed has maintained its charted course through the election, whether that was tightening as in 2004, cutting in 2008 or remaining on hold as in 1996, 2012 and 2020, according to a research report by Wells Fargo released in February.

Further, since 1994, the Fed adjusted its policy rate roughly the same number of times in presidential election years as in non-election years, the report said.

A separate research note by Barclays also found "no compelling statistical evidence that Federal Reserve policy is conducted differently during presidential elections."

Going forward, McBride said, "what will influence what the Fed does is what is happening in the broader economy."

And yet, Fed board members are nominated by the president and must be approved by the Senate. Powell will conclude his second four-year stretch as chair in 2026 — opening the door to a potential change in leadership — and, possibly, the direction of monetary policy — smack in the middle of the next presidential term.

The Trump campaign did not respond to CNBC's request for comment.