More people in California could be detained against their will because of a mental illness under a new bill backed Wednesday by the mayors of some of the nation's largest cities, who say they are struggling to care for the bulk of the country's homeless population.

Federal data shows nearly one-third of the country's homeless population lives in California, crowding the densely populated coastal cities of the nation's most populous state. California lawmakers have given local governments billions of dollars in recent years to address this, but often with mixed results that recently prompted a public scolding from Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom.

Local leaders say their hands are tied in many cases because the people who need the most help refuse to take it. A state law allows courts to order people into treatment, but only if they are “a danger to themselves or others.” This new proposal would expand that definition to include people who, because of a mental illness or an addiction to illegal drugs, are not capable of caring for themselves or protecting their own safety.

“I'm often asked as mayor, 'why aren't you doing something about this person who is screaming at the top of their lungs on the street corner'? And I say, 'well, they're not a threat to themselves or to others' — and that rings hollow,” said Todd Gloria, Democratic mayor of San Diego, the nation's eighth largest city, with nearly 1.4 million people. “Our current rules sets the bar so high that we can't help that individual.”

Lawmakers have tried for years to expand the definition of gravely disabled — including a proposal last year that passed the Senate but never made it out of the state Assembly.

Deb Roth, senior legislative advocate with the advocacy group Disability Rights California, said her organization opposes the bill because it would expand the law “in a way that is highly speculative and will lead to locking more people up against their will and depriving them of fundamental rights, including privacy and liberty.”

“The response should be to invest in greater voluntary, culturally responsive mental health services and supports to help people get on a path to recovery while maintaining their dignity and civil rights,” she said.

California

State Sen. Scott Wiener, a Democrat from San Francisco, said most homeless people do not have mental health or addiction problems, but a small percentage of people living on the streets are so severely debilitated that they are not capable of making decisions for themselves.

“We can't just plop them in a home and expect them to succeed,” he said. “Despite what some advocates say, it is not progressive to just sit by and let people deteriorate, fall apart and ultimately die on our streets.”

Get a weekly recap of the latest San Francisco Bay Area housing news. >Sign up for NBC Bay Area’s Housing Deconstructed newsletter.

The bill is the latest attempt to update California’s 56-year-old law governing mental health conservatorships — an arrangement where the court appoints someone to make legal decisions for another person, including whether to accept medical treatment and take medications.

The issue drew the spotlight recently with the case of pop star Britney Spears, who was under a controversial conservatorship run by her father and an attorney before it was dissolved in 2021. But advocates said that was a different kind of conservatorship, with different rules than the ones lawmakers are trying to change.

Advocates point to the case of Mark Rippee, a Vacaville man who lived on the streets for years while his family pleaded for him to get help. He died in November.

“We do not want to bring anyone into the hospital who doesn’t need to be hospitalized. But when that time comes, and we cannot protect them, it is devastating,” said Emily Wood, chair of the California State Association of Psychiatrists Government Affairs Committee.

Last year, Newsom signed a law that created a new court process where family members and others could ask a judge to come up with a treatment plan for certain people with specific diagnoses, including schizophrenia. That law would let the judge force people into treatment for up to a year. This new bill would go beyond that by applying to more people — with a particular focus on people who are in imminent danger.

“This will hopefully just deal with a smaller subset of the population who struggles with mental health issues,” Eggman said.

Advocates said Wednesday they think they have enough support to get the bill passed this year, citing new leadership of some key legislative committees in the state Assembly.

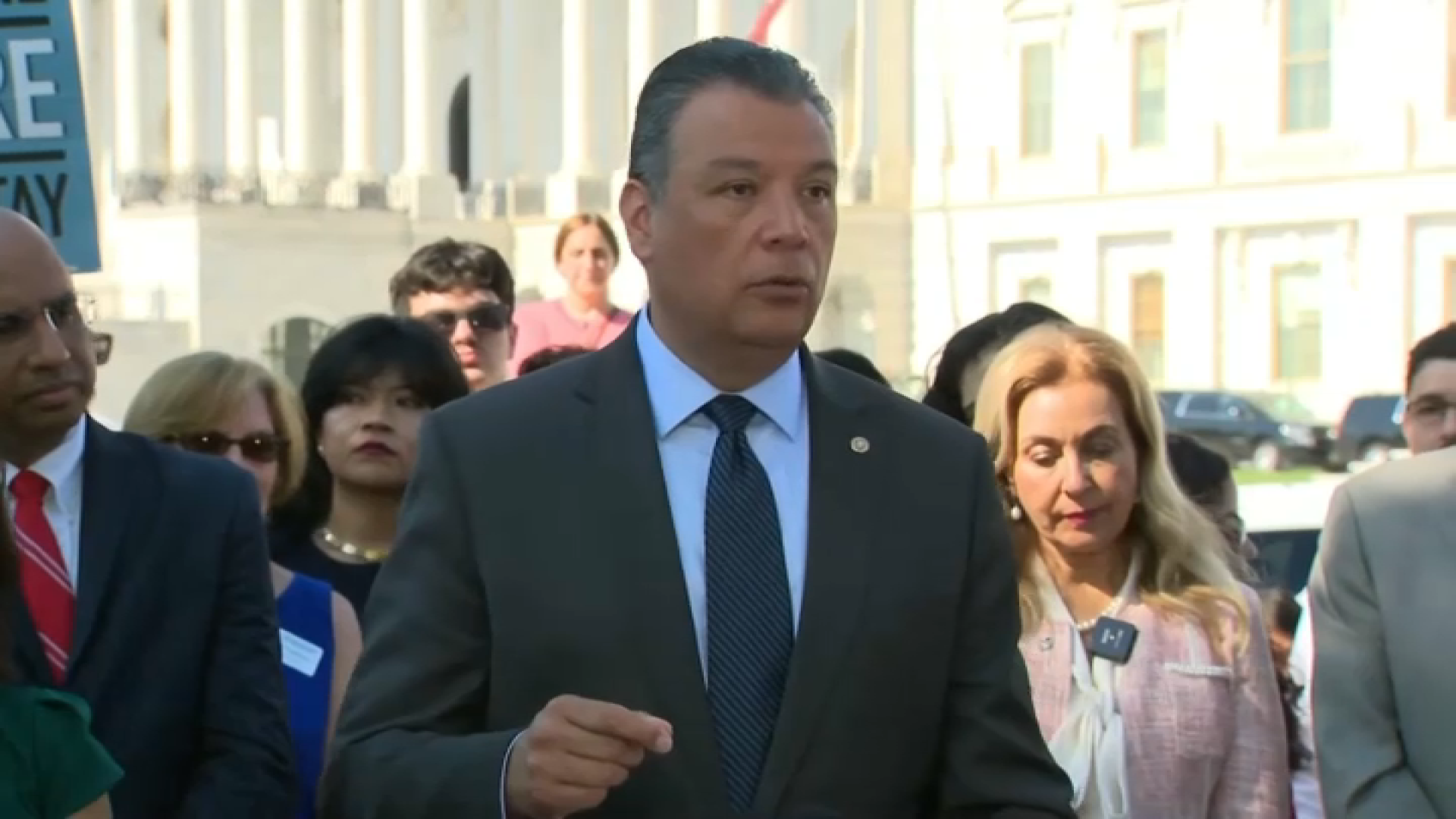

Assembly Republican Leader James Gallagher spoke during Wednesday's news conference, a rare showing of bipartisanship:

“We have this cycle of devastation, of human devastation on the streets, of people who we all know need help and literally cannot get it because of the current law. It needs to change.”