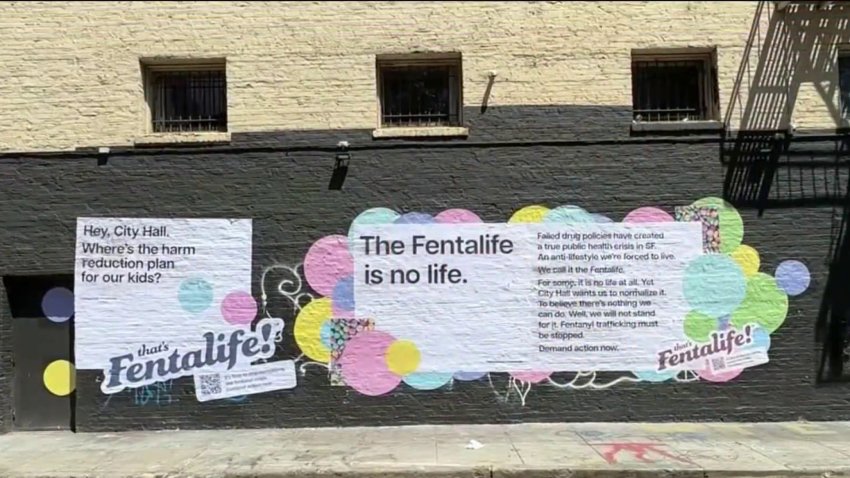

The California Department of Public Health and multiple Bay Area counties are seeking to educate the public about the fentanyl crisis currently hitting the state and nation. The below explainer provides answers to some basic questions about the topic, which cost nearly 6,000 lives in California in 2021.

What is fentanyl?

Fentanyl is a powerful synthetic opioid. It is 50-100 times more potent than morphine and can be fatal in amounts as small as a few grains of sand, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA).

Opioids are the class of drugs that include forms that are non-synthetic, meaning they are naturally occurring, and synthetic, which means they are manufactured chemicals that act in the same way, according to Johns Hopkins Hospital.

Examples of non-synthetic opioids, which are derived from the poppy plant, include heroin and morphine, according to the Mayo Clinic. Examples of synthetic opioids include fentanyl, OxyContin, and Vicodin.

Opioids are used to treat severe pain, by prescription. They block pain receptors in the brain. There is no medical use for heroin, which is an illegal narcotic. Other opioids, both synthetic and non-synthetic, are approved for use by the FDA to treat severe, acute pain, often following surgery, during cancer treatment, or during end-of-life care, according to NIDA.

Fentanyl is prescribed in the U.S. under brand names such as Duragesic and Actiq, according to the Food and Drug Administration.

Illicitly manufactured fentanyl can come in both liquid and powder form, according to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration.

What is "rainbow fentanyl?"

Get a weekly recap of the latest San Francisco Bay Area housing news. Sign up for NBC Bay Area’s Housing Deconstructed newsletter.

Rainbow fentanyl is just dyed fentanyl.

It is increasingly found in pill or powder-brick form to which colorful dye has been added. The DEA believes the trend is an attempt by cartels to market the drug to children.

What is the fentanyl crisis?

Cities and counties across the country are experiencing steady increases in fatal overdoses attributed to fentanyl, especially among young people, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and California Department of Public Health (CDPH).

The federal government declared the crisis a public health emergency in 2017.

In the Bay Area, San Francisco reported a slight decline of fatal opioid overdoses in 2021 from the previous year, but still had far more deaths per 100,000 residents than any other Bay Area county, according to data from the CDPH overdose dashboard.

Age-adjusted rates are used in health data to equalize the age distribution in different populations to compare against a single standard. The California Department of Public Health uses the United States 2000 population figures. The adjusted number represents the death rate per 100,000 people in a population with an equalized age distribution.

In 2021, the last full year for which data is available, San Francisco led all Bay Area counties in both total fatal overdoses and in the death rate using a standard, age-adjusted population, per 100,000 people. The city recorded 435 deaths from all opioid overdoses, with an age-adjusted death rate of 42 per 100,000 people.

Sonoma County was second in the standardized death rate, at 25.6 per 100,000 people. The county recorded 122 total fatal opioid overdoses in 2021.

Third was San Joaquin County, with 143 total fatal overdoses, or an age-adjusted rate of 18.7 deaths per 100,000 people.

On the other end of the spectrum, with 27 total overdoses in 2021, Monterey County had the lowest death rate, at an age-adjusted rate of 5.6 deaths per 100,000 people. Santa Clara County had a rate of 7.7 deaths, with a total of 154 fatal overdoses in 2021.

Overdoses are being driven both by people using fentanyl intentionally and people using other drugs that have been either combined with fentanyl or are counterfeit pills that include fentanyl. Counterfeit pills can appear to mimic well-known prescription drugs like Adderall and Valium, according to the DEA.

Epidemiologists have defined three prior waves of addiction that impacted the nation, according to the San Mateo County Health Department. The first was in 1996, as synthetic opioids became prevalent and over-prescriptions increased.

In 2010, users who had become addicted turned increasingly to heroin, fueling a second wave of addiction. The fentanyl crisis escalated in 2013 and 2014 as the drug became increasingly overprescribed and smuggled in from overseas.

There is now a fourth crisis being defined, as fentanyl is increasingly being combined with stimulants and other drugs, including xylazine, a large-animal tranquilizer that is not approved for use in humans. The DEA and CDPH both issued recent public health alerts warning of the use of xylazine.

"Xylazine is making the deadliest drug threat our country has ever faced, fentanyl, even deadlier," DEA Administrator Anne Milgram said in a statement.

What caused the crisis?

In 1996, pain was redefined in the medical community as a fifth vital sign. This ushered in a huge change in the health care industry. Pharmaceutical companies became heavily invested in what was a growing sector of the health care system: pain management, including chronic pain management. That same year, Oxycontin was introduced and marketed as a way to control chronic pain.

Writing for the peer-reviewed medical journal Clinical Therapeutics in 2013, authors Dr. Natalia E. Morone and Dr. Debra K. Weiner said more basic pain-management education was needed by prescribing doctors:

"In clinical practice pain as the 5th vital sign has proven to be more complex to assess, evaluate, and manage than originally anticipated. It has also had some serious consequences which were never intended. Associated with the national push to adequately manage patients in pain has been a rise in prescription opioids as well as a rise in opioid related death. Guided by pain as the 5th vital sign mandates, patients report pain and expect their providers to respond. Many clinicians do not know what the appropriate response is because they lack adequate education in the approach, examination, and management of patients in pain."

Pain management for even basic medical procedures was creating more and more addicts, who turned to other means to satisfy their addiction after their medical treatment ran its course. Fentanyl is the latest form of opioid being abused, but it is much more potent and deadly than other forms of the drug, bringing renewed urgency to the overall problem of opioid addiction.

Where does fentanyl come from?

Outside of abuse of prescription fentanyl, according to the DEA, illicit fentanyl mainly comes from China. Additionally, base chemical ingredients are shipped to Mexico and manufactured there by drug cartels, which then smuggle the drug into the United States, often compressed into counterfeit pills that mimic more well-known brands.

Who is dying from fentanyl?

People mainly between the ages 10-49 have been dying of overdoses. Black people are being more disproportionately affected in the current trends. Earlier waves of opioid addiction impacted white people more disproportionately, according to the San Mateo County Health Department.

How is the health care system handling the issue?

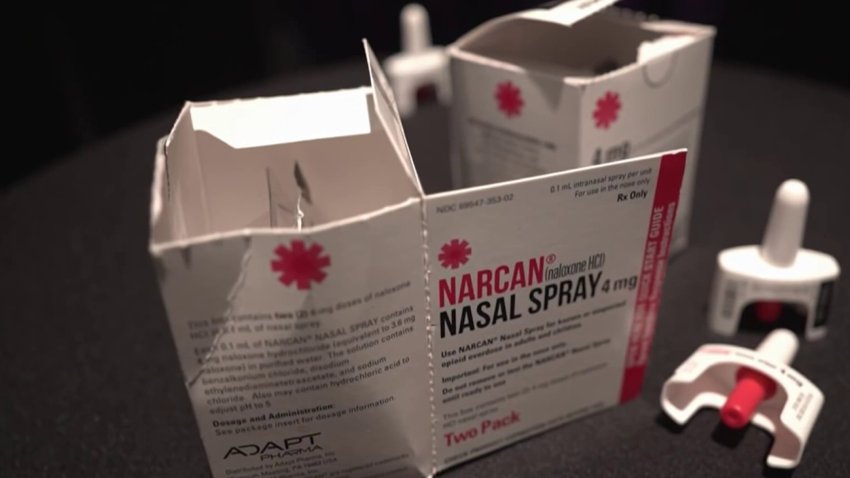

There are two priorities in the health care system: one is preventing overdose deaths through emergency antidotes like Narcan, a brand name for naloxone, which can be used to save a person suffering a fatal overdose.

The most effective "gold standard" treatment is called medication-assisted treatment, known as M.A.T., and involves using medications like methadone to try to stop the addiction cycle.

The other is to make treatment options, including M.A.T., more available and affordable, including in jails and prisons.

San Mateo County is seeking to combine M.A.T. with coaching and counseling, and support from community resources like more housing options.

Health care regulators have also sought to dramatically decrease the number of opioids prescribed by doctors. The CDC announced in 2020 that prescriptions had fallen from a peak in 2012 of 255 million prescriptions nationwide, the equivalent of about 81 prescriptions per 100 people, to about 142 million in 2020, about 43 per 100 people.

What is law enforcement doing?

At the federal level, the U.S. Department of Justice and the Food and Drug Administration have tried to reduce over-prescriptions by doctors.

The DOJ also recently finalized a financial settlement with the Sackler family, the owners of Purdue Pharma, which created Oxycontin and continued to aggressively market the painkiller to doctors despite knowing about its highly addictive nature.

The DOJ has also sought to put pressure on Mexican drug cartels to stop the flow of fentanyl across the border. In April, leaders of the Sinaloa cartel were indicted by the DOJ on charges of trafficking fentanyl, weapons, and money laundering.

"Today, the Justice Department is announcing significant enforcement actions against the largest, most violent, and most prolific fentanyl trafficking operation in the world - run by the Sinaloa Cartel, and fueled by Chinese precursor chemical and pharmaceutical companies," said Attorney General Merrick Garland in an April 14 statement. "Families and communities across our country are being devastated by the fentanyl epidemic. Today's actions demonstrate the comprehensive approach the Justice Department is taking to disrupt fentanyl trafficking and save American lives."

In April, Gov. Gavin Newsom assigned the California Highway Patrol and California National Guard to a joint task force with local authorities in San Francisco to target some of the hardest-hit areas in the crisis, including the Tenderloin neighborhood.

"The fentanyl crisis is a serious threat to public health and the safety of our communities -- and addressing this crisis requires a multifaceted, collaborative approach," said Attorney General Rob Bonta in a statement at the time. "The California Department of Justice works every day to combat the fentanyl crisis, from seizing illicit fentanyl through our ongoing enforcement efforts to bringing California billions of dollars through our lawsuits and investigative efforts to hold the opioid industry accountable."

What are federal lawmakers doing?

The U.S. Senate is considering multiple bills to address the crisis.

Sen. Rick Scott, R-Florida, has introduced to bills related to stopping the trafficking of the drug. One bill would require more regular inspections by U.S. Customs and Border Protection, and the other would enhance electronic data tracking from international shipments through the U.S. Postal Service.

Two senators, one Republican and one Democrat, introduced a bill in May that would further instruct the Treasury Department to find ways to sanction and disrupt shipments from transnational actors. The bill is called the Fentanyl Eradication and Narcotics Deterrence Off Fentanyl Act, also known as the FEND Off Fentanyl Act. The bill unanimously passed the committee on banking, housing and urban affairs in June.

What are state lawmakers doing?

California is considering Senate Bill 641, introduced by Sen. Richard Roth, D-Riverside, and sponsored by Assemblymember Matt Haney, D-San Francisco, among others. The bill would expand the state's Naloxone Distribution Project to increase the dosage of the life-saving drug, seek additional versions than the sole, current supplier, and make it more widely available to cities and counties with funding through the state.

The Assembly public safety committee held a special meeting in May and advanced four bills on the subject, including one to increase penalties for dealers of the drug.

The CDPH Substance and Addiction Prevention Branch partners with local medical providers to increase awareness and offer prevention and disruption strategies, which are bolstered by the data monitoring and collection the branch undertakes. The data also informs the public through the online overdose dashboard.

What are counties doing?

Counties are seeking to make the lifesaving drug Narcan more widely available and are lobbying for generic versions to become available. They are supporting state legislation that would provide funding for the drug statewide.

Counties are also seeking to increase the availability of chemical test strips, which can help users identify the presence of fentanyl before using drugs.

Counties are trying to make treatment options more affordable and available by investing in counseling, rehabilitation and medically assisted treatment options.

Counties like San Mateo County are also seeking to increase the availability of "wet" or "damp" housing options for those experiencing homelessness, which would allow people to obtain shelter without being sober.

And counties are trying to educate the public, especially youths, parents and school personnel.

Are pharmaceutical companies being held liable for over-prescriptions?

The makers of Oxycontin, Purdue Pharma, settled a class-action lawsuit brought by multiple states that alleged that Purdue knew about the addictive qualities of prescription opioids but continued to push doctors to prescribe them at high rates.

The company agreed to pay $6 billion to nine states, including $486 million to California to be used for opioid treatment programs.

"The opioid crisis has left a trail of pain, grief and destruction across the nation that will leave its mark on generations to come. Its ringleaders -- Purdue Pharma and the Sackler family -- bear responsibility for causing much of this grief," Bonta, the state attorney general, said in a statement in May.

Bonta highlighted the fact that Purdue executives pleaded guilty to felony misbranding of OxyContin but continued selling and marketing the drug.

An even larger settlement with Janssen Pharmaceuticals, parent company of Johnson & Johnson, and three major distributors was agreed to in 2021 and finalized last year. The companies agreed to pay $26 billion through 2038. California is expected to receive about $2.05 billion, according to the California Department of Health Care Services.

Walgreens also settled a federal lawsuit in May with the City and County of San Francisco that will see the company pay $230 million over 14 years to compensate for lacking safeguards against distributing high numbers of opioid prescriptions.

How do I administer Narcan?

Narcan is an antidote for overdose. The FDA made the drug available without a prescription in April in an attempt to make it more readily available.

The following instructions are from Adapt Pharma, the makers of Narcan, and are approved by the FDA:

1. Lay the person on their back

2. Remove the Narcan nasal spray from the box and remove the tab with the circle to open the spray bottle.

3. Hold the bottle upright with your thumb on the red plunger and position the nozzle in between your forefinger and middle finger.

4. Tilt the person's head back, providing support under the neck with one hand. Use the other hand to gently place the nozzle into one nostril, stopping when your fingers touch the bottom of the person's nostril.

5. Press the red plunger firmly and administer the entire dose into one nostril only.

6. Remove the spray bottle from the nose after using.

7. Move the person into the "recovery position," which has the person lay on their side, tucking both hands under the head for support and extending the leg that is on top in that position slightly forward to stop the person from rolling onto their stomach.

8. Get help immediately. If the overdose victim does not respond to the first dose, Narcan can be safely administered every 2-3 minutes, as many times as is necessary.

9. Put the empty spray back into its box and discard away from children.

How to respond to a suspected overdose?

1. Shake the unresponsive person and shout their name

2. Call 911 if unresponsive

3. Administer naloxone or Narcan

4. Perform chest compressions and mouth-to-mouth CPR

5. If the patient is still unresponsive, repeat steps 3-5. Stay with the patient.