Some of the rainiest weeks since the Gold Rush left the state and the Bay Area drenched, but didn't technically end California's drought.

Here's what to know about how the state decides what's a drought and what's not.

The Golden State is, of course, no stranger to droughts: we've been living through them for most of the last decade. They can mean big wildfires, bad growing conditions for farmers, and water restrictions.

Three Kinds of Drought

Droughts can be measured in a lot of different ways, but there are three basic kinds of drought that scientists look at.

- A meteorological drought means a lack of rainfall. In this case, those big storms left California doing just fine in that department.

- An agricultural drought generally means there's not enough moisture in the soil, which makes it hard for plants to grow.

- A hydrologic drought means that rivers, streams and groundwater are lower than normal.

The U.S. Drought Monitor

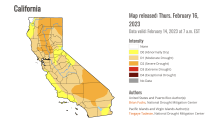

All three of those factors go into something called the U.S. Drought Monitor. It's a map that comes out every week on Thursdays, and you might've seen it in our weather forecasts here at NBC Bay Area.

It breaks up the country into color-coded areas — from yellow, which is just abnormally dry, all the way to a deep red color that signifies an "exceptional" drought — the kind where entire crops die off, and wells run dry.

Get a weekly recap of the latest San Francisco Bay Area housing news. >Sign up for NBC Bay Area’s Housing Deconstructed newsletter.

Local

Right after the heavy rains in January 2023, the U.S. Drought Monitor map showed most of California in a "moderate" drought, and left a few places in a "severe" drought — the kind where fire danger is high, and fire season lasts longer.

The rains did manage to eliminate the areas of "extreme" drought, which is when fire season can last year round.

Reservoirs and Snowpack

The U.S. Drought Monitor is a national index. But here in California, there are other things state regulators look at.

First, there are reservoirs, including the big ones that are part of the State Water Project. Even the biggest rainstorm is not enough to refill the state's largest man-made lakes after a multi-year drought — but that incredibly wet January got close, and brought them to 96 percent of their historical average.

Then there's the Sierra snowpack, which actually makes up 30 percent of the state's water storage. A month of storms at the start of 2023 put that above its historical average, at 138 percent by mid-February.

But the more important snowpack measurement happens in April, at the end of snow season, because snow can start to melt early during a warm winter. Water managers want it to pile up and stay frozen, so it can melt in the summer, and run off into creeks and streams that feed the state's water system.

Wells Running Dry

In just the last decade, the state started tracking another indicator: problems with wells — especially in areas that depend heavily on groundwater, like the Central Valley. Some communities get most or all of their water from huge underground lakes that both homes and farms rely on, and those subterranean bodies of water can take a lot longer to fill back up than lakes on the surface.

In the summer of 2022, there were more household wells that literally ran out of water than any other quarter since state authorities started keeping track. And even after the big storms a few months later, almost two-thirds of the wells the state uses to measure and monitor groundwater were below their normal level.

It all means the wet start to 2023 got California closer to being out of a drought, but not all the way there. Droughts are stubborn, and even those unprecedented storms left the state needing more rain and more cool temperatures to officially get out of drought status.