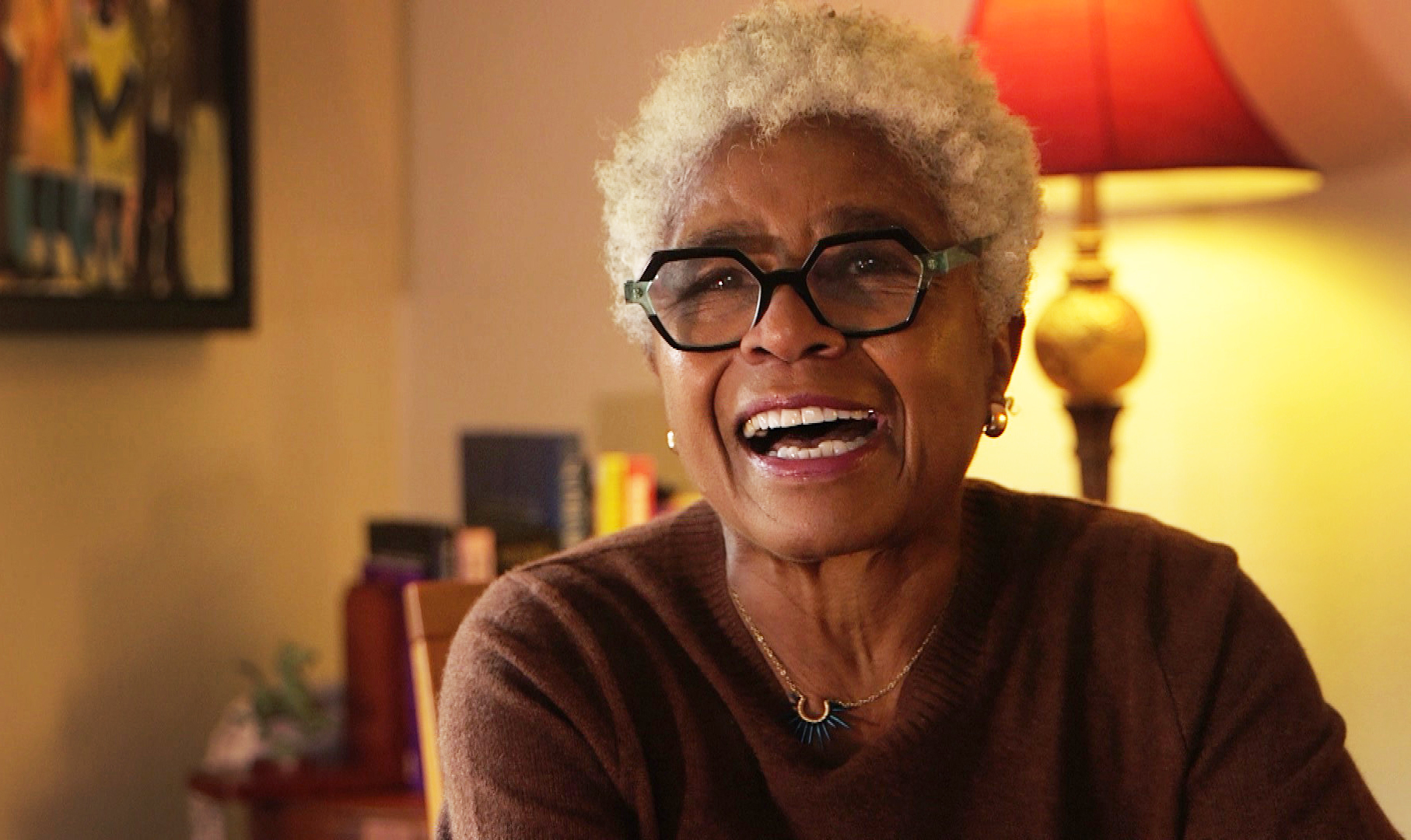

The crowd of high school students from San Rafael crowded around Felecia Gaston as she led them through her exhibit chronicling the history of the tiny Marin County community of Marin City, an exhibit she’s been lovingly assembling for the last three decades.

Gaston’s traveling exhibit is currently on display in the Marin County Board of Education building in San Rafael running through the end of May.

Since moving to Marin City from Georgia many years ago, Gaston has become the champion of the somewhat overlooked Marin City community tucked in between Mill Valley and Sausalito. To many, the only hint of its existence is the highway signs announcing Marin City/Sausalito.

“I have met people who are in their seventies,” Gaston said in between student tours, “say ‘I’ve been living in Marin County all these years and I had no clue about this history.’”

Inside the office hallways of the education building, photos stretching along the hallways showed the Black workers who relocated from the South during World War II to labor in Sausalito’s Marinship yard. Industrial equipment like the ones used to build more than 90 ships that came out of the shipyards stretched along a table. Identity cards of the Black workers put faces to those who silently aided the nation’s massive war effort.

Among the artifacts collected by Gaston was the suitcase of the late Annie Smalls who took a train from Louisiana to Marin County to work in the shipyards — riding the suitcase all the way in the overcrowded train. Smalls was among the workers who took up residence in what was intended to be temporary worker housing in Marin City — the town that sprung up to house the Marinship workers.

“When I first started working in Marin City since the late 80s,” Gaston said, “I had a chance to meet the original Marinship workers and they started sharing their stories with me.”

Gaston is now in turn sharing those stories with Marin County students through tours of her exhibit. She tells personal stories of the people who came to Marin seeking better lives. Her tour tells of how those Black families lived for upwards of 18 years in Marin City housing meant to last four years — even as the buildings exceeded their lifespan and began to crumble.

While white families were offered loans to buy homes in the area, the same offers weren’t extended to Black families. Marin City became a containment zone for those left behind by progress once the war ended and the shipyard folded. Gaston showed the students a newspaper article detailing how Marin County eventually resorted to burning down the dilapidated homes as a quick means of demolition.

Get a weekly recap of the latest San Francisco Bay Area housing news. Sign up for NBC Bay Area’s Housing Deconstructed newsletter.

“The hope is that they get a better understanding about the true history of the Black residents,” Gaston said as the students wandered among her artifacts.

For most of the students, Gaston’s tales about the small community just 15 minutes down the highway came as a surprise.

“I think it’s interesting after living here my whole life how I’ve literally never heard about it,” said student Evelyn Noyes following Gaston’s tour. “It’s literally never been brought up by any of my teachers.”

As founder of Performing Stars, the non-profit Marin County organization aimed at teaching arts and performance to low-income kids, Gaston has a long nurtured a keen interest in the balance of opportunities. The stories of Marin City and its hardscrabble, patriotic residents who came West seeking better lives only to be abandoned in a region of extreme wealth, is a story she believes needs to be heard.

“They contributed to the war effort, they contributed to the social life,” said Gaston. “But they was also dealt with a lot of discrimination.”

During the war, Gaston said there were 20,000 Black residents in Marin City. As of 2023, the number stood at 790. Gaston hopes her collection will eventually land in a permanent museum devoted to the story of Marin City, to help preserve its and identity to a community that exists beyond the road signs.

“We need people to know the real story,” Gaston said, flanked by her artifacts. “It’s a California Black history story — it’s a national story.”