While two separate teen suicide clusters in Palo Alto made national headlines and prompted a 2017 study by The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, an NBC Bay Area investigation last year found many Northern California school districts have dozens, if not hundreds, of students each year who hit mental health crisis points and are placed on 5150 holds at local psychiatric hospitals.

The 5150 hold refers to the law code used to identify people at risk of harming themselves or others, and can lead to an involuntary hospitalization for up to 72 hours.

But NBC Bay Area’s investigation also found most of the Bay Area’s largest school districts actually have no idea how many of their students are involuntarily hospitalized each year for mental health issues. At the time, Palo Alto Unified School District was one of the many districts that said it could not provide 5150 data. The district also declined multiple interview requests to discuss the issue.

But last year, new Assistant Superintendent Yolanda Conaway said the district is now keeping better track of that data, and over the past few years, has put other measures in place to help ensure students get help before reaching a crisis point. The district opened wellness centers for students a few years ago, and is partnering with mental health experts at Stanford University.

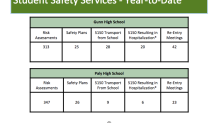

According to data recently provided by the district, Gunn High School had 28 5150 transports from school between August 2017 and March 2018. Twenty of those resulted in a student being hospitalized. At Palo Alto High School, the district reported nine 5150 transports and six hospitalizations.

Conway said the district is in better position than ever to intervene before students reach the point where they may need to be hospitalized.

“My message is let’s get to the issue before it gets to crisis level,” Conaway said. “Let’s intervene early, identify those students who need help early and make sure that we’re providing the appropriate support.”

Conaway said much of the dialogue around the issue centers around stress at school, such as excessive homework or the rigors of advanced placement courses. She acknowledged those factors can contribute to mental health issues for students, but said people often focus too much on the low hanging fruit instead of the complete picture.

Local

“We will certainly make some headway by looking at things like homework and class sizes and rigor, but if we really want to get a hold of making sure that we’re providing support, we have to find a way to build resiliency and connectedness within the school environment, helping kids cope,” Conaway said.

Early last year, NBC Bay Area sent surveys to several dozen of Northern California’s largest school districts. Just eight of the 21 districts that responded could tell NBC Bay Area how many of their students were placed on a 5150 hold during the 2016-17 school year. Across those eight districts, students were hospitalized for mental health issues at least 455 times. That figure is likely low, as the data capture only incidents that occur on school campuses.

Aurora Vaughn, who dealt with mental health issues at Gunn High School from her sophomore year until she graduated in 2017, said she was fortunate to receive help before she reached a crisis point, thanking her dance coach and her parents for intervening.

“I love academics, I love being in a stimulating environment like that,” Vaughn said. “Sometimes I felt overwhelmed by it at the same time.”

Vaughn, now a sophomore in college majoring in dance, said every student has unique challenges. For her, a large workload at school and a strenuous dance schedule left her feeling exhausted and anxious.

“It was not just one cause,” Vaughn said. “I was fatigued, and I was super anxious, and through that, I started to lose weight. Those are physical signs of the depression that I was feeling. I was lucky enough to have my parents catch on to that and my dance teacher catch on to that.”

Vaughn said that intervention led her to therapy, which provided her with coping mechanisms to help manage her stress and anxiety.

Losing some of her peers to suicide, Vaughn said, weighed heavily on her and her classmates.

“Losing peers, regardless of whether or not you know them, is jarring to say the least,” she said. “It definitely contributed to my mental health and the difficulty I had [sophomore] year.”

Conaway said talking about suicide can be difficult, but it’s critical that students feel comfortable discussing those feelings out in the open.

“I think it’s extremely important for the adults in the equation to allow students to engage in this conversation about what they need in terms of support,” Conaway said. “Sometimes as adults, we get a little hesitant because we don’t want to re-traumatize.”

Although Vaughn struggled with mental health issues throughout high school, she said she felt supported and hopes the community keeps chipping away at the stigma surrounding mental health.

“I think sometimes Palo Alto is misconstrued as this awful environment for kids and for students,” Vaughn said. “It’s really situational and personal. I do think there are things everyone can do to change the environment that they’re in, but there’s no one person to blame, there’s no one community to blame. It takes a village. And everyone just needs to step up and help.”

A new documentary, directed by former NBC Bay Area producer Liza Meak, looks back at the Palo Alto high school suicide clusters through the eyes of six Palo Alto Unified School District students grappling with the loss of their peers and coping with day-to-day life in one of the region’s most prestigious school districts. "The Edge of Success" explores how factors such as stress, anxiety, depression, and sleep-deprivation contributed to 10 Palo Alto students taking their own lives since 2009.

If you or anyone you know is in crisis, someone is available to talk and listen 24 hours a day. The suicide prevention hotline is 1-800-273-8255.