Today, April 30th 2015, marks 40 years since the fall of Saigon and the official end to the Vietnam War. Not long after the end of the war, my parents began the long and dangerous journey from Saigon to America.

I’ve often thought of what my life would have been like if my parents hadn’t chosen to risk their own so many years ago. I’ll never know. But I think it’s that unanswerable question that has driven me since I was a little kid.

Work hard, make the most of your opportunities, be curious about your world, relish and appreciate every day because you live in a free country where just the air you breathe allows you so many more chances than anyone else living anywhere else.

I’m not on a soapbox for American exceptionalism, but as a Vietnamese refugee, I can say with certainty that I owe everything I’ve achieved to the freedom afforded to my family and I when we first arrived in this country in March of 1980.

Gallery: From Saigon to Eugene, Oregon

My family could have emigrated to Europe or Australia, but they held out for the chance to come to America rather than any other country. I asked my father, Huy, why. “Oh we read, we know,” he said. “We know that we have a good life because this is America. We have a lot of freedom and opportunity.”

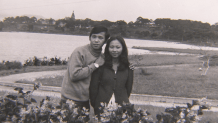

My parents married in Vietnam in 1976, just one year after the war. They recall it being a solemn ceremony. They have just one photo from that time. Many people were still in mourning, wondering what their lives would be like after the South Vietnamese army lost, the American troops left, and the communist Vietnamese took over.

It wasn’t until four years after the war, living under a communist government, that my parents had the chance to escape. They knew a fisherman, a family friend of my mother’s. On May 4, 1979, my parents, my two uncles, my great aunt and I got on that boat. I was 8 months old, a bald headed baby, on the first adventure of my life.

Malaysia

It was treacherous. On the way to the boat, my family was stopped by Vietnamese police. It was suspicious that they already knew where we were going, but after they robbed us of gold and jewelry, somehow we were allowed to continue, instead of being jailed for trying to escape.

We were headed for the open ocean and, eventually, a refugee camp in Pulau Bidong, Malaysia. 68 souls were on board, including 18 children. Pirates from Thailand trolled the waters, knowing refugee boats were easy targets. My parents remember the encounter—men scrambled aboard pretending they were offering help, then one man fired a gun, others brandished knives, and they demanded everyone’s valuables.

Again, we were lucky. They only robbed us. Many other boat people have reported stories of murder and rape, terrible brutality.

The seas were calm and after the pirates left, the rest of the voyage was peaceful. We arrived in Malaysia, joining 50,000 people crowded onto a tiny camp the size of a football field.

Refugees were photographed, assigned ID numbers, and if they were lucky, still had enough money or valuables to trade for a shelter. Every day, rice, mung beans and water were rationed, along with half a cabbage a week. Once in a while we bought fish from local fishermen.

That camp was where I learned to walk.

We had the choice to go to several countries: Canada, France, Brussels, Australia. All were generous and accepting refugees from Vietnam. If you chose one of those countries, you could get off the island much faster, sometimes in just a few months.

“We thought America would be best,” my dad said. “Bigger and better so yeah, we wait[ed].”

My mother, Lien, had worked for the Saigon branch of Holt International Children’s Service, the United States’ first international adoption agency, based in Eugene, Oregon. When Saigon fell in 1975—she and many Holt staffers in Vietnam helped babies and children, many of them orphans, escape the country in what would later be called “Operation Babylift.”

Now, it was her turn to request help. My mother wrote a letter to Holt and explained that we had escaped Vietnam and were now in a refugee camp, in limbo. She said she had worked for Holt in Saigon. Could Holt sponsor us to America?

The Ware Family

When Wannell Ware, a Holt staffer, received that letter, it was not a question of how or if they would sponsor us.

“It was why not?,” Wannell said. “I opened the mail that day and I read that letter and that’s it as far as I’m concerned. They’re coming.”

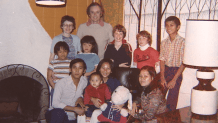

Wannell and her husband Don Ware had a special connection to Holt. Not only did Wannell work there, the couple had also adopted three children through Holt, adding to their two “homegrown” children. Long before it was popular, the Wares adopted two children from Korea and one from Vietnam.

Through their generosity, and the kindness of many people at Holt and two churches in Eugene, my family finally came to the U.S.

We arrived in March of 1980, first touching down at San Francisco International, then taking a bus across the Golden Gate bridge to Travis Air Force Base. My parents will never forget their first meal in America.

“Fried chicken with mashed potatoes with corn bread. And everybody liked it because it was different,” my dad said. “Some went back for seconds.”

Everyone got a thick jacket and then back onto a plane the next morning, this time headed to Eugene, Oregon, to start our lives in the United States.

Recently I had the chance to re-connect with the Ware family, and some of the former and current staff from Holt. We exchanged long overdue hugs, and I thanked them for their kindness and generosity in welcoming and supporting a family from half a world away.

This is part one of a three-part series on Vicky’s journey from Saigon to San Jose. Join her and Robert Handa on his talk show “Asian Pacific America” for the full report on May 17th at 530AM on NBC Bay Area or 6PM on Cozi TV, Comcast 186. Follow Vicky on Twitter @VickyNguyenTV or Facebook for updates.