Fifty-seven violins arrived in the Bay Area last week, wooden ambassadors carrying with them the darkest chapter in world history — the Holocaust.

The violins are among a collection amassed and restored by an Israeli father and son in a project known as Violins of Hope. The violins were all played by European Jews in the Jewish ghettos and Nazi concentration camps of World War II. The collection is traveling the world, being played in concerts and sitting as the centerpiece of lectures and exhibits examining the power of music in the face of unbridled bigotry and hatred.

“These instruments have been there, have seen most of what most of their owners seen,” said luthier Avshalom Weinstein, who along with his father Amnon Weinstein restored the instruments. “Unfortunately most of the owners are already dead so they cannot talk and tell their stories, but the instruments can.”

An exhibit of 20 of the violins opened Friday in a gallery in San Francisco’s War Memorial building where the public can closely inspect them and soak up their history, some bearing intricate inlays depicting the Star of David as well as the scars of their travels.

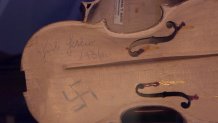

Amnon Weinstein began collecting the instruments in the 1990s, restoring as many as he could get his hands on. The father and son appeared at the War Memorial building for the opening of the exhibit last Friday. In addition to the violins the pair restored to playing condition, Avshalom showed a row of violins that remained unrestored, including a disassembled violin with a Nazi symbol scrawled inside the body.

“If we repair it you will never be able to see,” said Weinstein, pointing to a penciled swastika next to a date of 1936. “This is a symbol and this is proof that Nazis and Nazi sympathizers are everywhere and in every profession.”

Stories by Joe Rosato Jr.

With the Violins of Hope project making its West Coast Debut, the instruments will be played in concert halls, recitals and other performances during the 8-week run. They’ll traverse across musical boundaries from classical to klezmer to Americana. Before visitors began to spill in for the opening of the War Memorial exhibit, violinist Rebecca Jackson summoned a haunting melody from one of the instruments — its dark, plaintive voice filling the exhibit hall.

“The vibrations are what create that beautiful sound,” Jackson said. “So thinking of all the vibrations that were created by so many different people and those that struggled through a lot of tragedy is very profound.”

The instruments lived lives, some prominently, before their owners were forced into ghettos and the camps. Often the musicians who carried their instruments to the camps were forced to perform for their Nazi captors. For some the chance to play music brought moments of distraction from the grim reality of the oppressive conditions. Auschwitz survivor Ben Stern recalled the soothing sounds of a violin greeting him as he returned to the camp each day after working as slave labor in nearby coal mines.

“I think it’s a story of resilience and hope and the power of music to heal,” said exhibit curator Lisa Coscino. “The power of music to protest, the power of music as propaganda.”

One of the violins in the exhibit was accompanied by a sign reading “German violin thrown from a train leaving Lyon.” It recalled the story of the violin’s owner who was among French Jews being shipped to a concentration camp in a train cattle car. When the train stopped the owner tossed the violin to some railroad workers saying he wouldn’t need the violin where he was going, shouting, “Take my violin so it may live.”

“The stories are the most compelling part of the exhibit,” said Coscino. “They’re stories of hope, they’re stories of conflict, they’re stories of deep sadness and loss.”

For musicians, the small, crafted wooden boxes carry the history of the suffering in their sound — the music evoking the joy and sorrow of their owners.

“I know it’s fanciful,” said Bay Area folk musician Suzy Thompson, who will play one of the violins in concert. “I believe that these fiddles do speak to us of what they’ve witnessed.”

To Avshalom Weinstein, the violins don’t just carry history. They are shouldering a message of hope and resilience, as well as poignant warnings about the Holocaust’s legacy of hate.

“If we don’t make sure it won’t happen again, it very well can happen again," Weinstein said.