Originally appeared on E! Online

How time flies when the world's gone mad.

Nicole Brown Simpson and Ronald Goldman were killed outside the front door of her Los Angeles condo while her children slept upstairs in June of 1994, a sickening crime that led to one of the defining cultural happenings of the late 20th century: People of the State of California v. Orenthal James Simpson.

The O.J. Simpson murder trial, that is.

Within days after the double murder of O.J.'s ex-wife and her friend Goldman — who was a waiter at the restaurant where Brown Simpson had dined with her family earlier that night and had dropped by to bring the glasses her mother had left behind — a whole new vernacular rocketed into the national consciousness: Brentwood. Rockingham. Bundy. Low-speed chase. Bruno Magli. DNA. Kardashian.

Simpson, who passed away at the age of 76 on April 10 following a cancer battle, pleaded "absolutely, 100 percent not guilty" on July 22, 1994. The jury was sworn in on Nov. 9, 1994, and opening statements wouldn't commence until January of 1995.

American Crime Story: The People v. O.J. Simpson: Fact v. Fiction

U.S. & World

By the time the verdict was read on Oct. 3, 1995, the Simpson trial had cost the city of Los Angeles upward of $10 million and was every bit the circus that you may or may not remember.

The basic facts are well-known. Prosecutors thought they had a slam-dunk case thanks to DNA evidence from blood collected at the scene of the crime and at Simpson's home two miles away.

Get a weekly recap of the latest San Francisco Bay Area housing news. >Sign up for NBC Bay Area’s Housing Deconstructed newsletter.

"That trail of blood from Bundy through his own Ford Bronco and into his house in Rockingham is devastating proof of his guilt," Deputy District Attorney Marcia Clark said in her opening statement.

Complicating the People's supposedly open-and-shut case, Mark Fuhrman, the detective who first spotted a blood-spattered glove outside Simpson's estate at 360 Rockingham Avenue that looked like one found near the bodies, had a history of using racist language and had boasted about beating up suspects.

Much to Clark and co-prosecutor Christopher Darden's disbelief, Simpson's defense team, led by Johnnie Cochran, dismantled the jurors' trust in the seemingly irrefutable DNA, and in the police who investigated Simpson — a trust already on shaky ground in the wake of the 1992 acquittal of four white police officers charged with excessive force after they were caught on video beating Rodney King, a Black man, on the side of an L.A. freeway.

And so, in the end, Simpson was found not guilty of murder. But a lot of screwy stuff happened before the world got to that point, nearly 29 years ago. Here's a sampling:

Close watch

O.J. Simpson met Nicole Brown in 1977 and divorced his first wife, Marguerite, in 1979. He married Brown Simpson on Feb. 2, 1985; their daughter Sydney was born eight months later, and son Justin was born in 1988.

"You guys never do anything," Brown Simpson told police when they arrived at the Simpson home at 360 N. Rockingham Ave. in L.A.'s posh Brentwood neighborhood, responding to a domestic abuse call in the the early morning hours of Jan. 1, 1989, according to reports about that night. "You never do anything. You come out. You've been here eight times. And you never do anything about him."

Simpson insisted he didn't beat Brown Simpson, only pushed her out of bed. Then, told he needed to go with the officers to the police station, he drove off instead. A few days later, Brown Simpson went to the station and said she didn't really want them to proceed with a prosecution, but she consented to out-of-court mediation.

On May 24, 1989, Simpson was sentenced to 24 months of probation, ordered to perform 120 hours of community service and pay fines totaling $470, and was told to attend counseling twice a week (he was allowed to do it by phone) after pleading no contest to misdemeanor domestic violence.

Brown Simpson eventually moved out with Justin and Sydney and filed for divorce in February 1992. They settled that October, with O.J. agreeing to pay her a lump sum of $433,750, plus $10,000 a month in child support, and she retained the title of a rental property. She eventually bought a condo at 875 S. Bundy Drive in Brentwood and moved there in January 1994.

All the while, Simpson was alternately threatening her and trying to get back together. According to prosecutors and witnesses, Simpson had stood outside and looked through her window on multiple occasions, including one time when she was having sex with a boyfriend. Per Jeffrey Toobin's 1996 book "The Run of His Life," in a diary entry from June 3, 1994, Brown Simpson detailed a recent threat from Simpson: "'You hang up on me last nite, you're gonna pay for this...You think you can do any f--king thing you want, you've got it comming [sic]..." and so on.

She called a battered women's shelter in Santa Monica on June 7, 1994, to lament that her ex was stalking her. Five days later she was dead.

Tinted window

TIME came under fire for darkening O.J's complexion when the publication ran his mug shot on the cover in June 1994, with critics arguing it was cheaply playing up the Black-male-murder-suspect angle and pointing out that Newsweek had run the photo without altering the color.

Managing editor James R. Gaines relayed in a statement posted on an AOL message board (remember AOL Time Warner?) that "no racial implication was intended, by TIME or by the artist" — but that yes, the photo given out by the LAPD had specifically been handed to an artist to turn into cover art for the story, which would include interpreting it as he saw fit.

"It seems to me you could argue that it's racist to say that blacker is more sinister," Gaines said, "but be that as it may: To the extent that this caused offense to anyone, I obviously regret it."

The publishing industry

Dozens of books have been written about this case, including Simpson's inexplicable 2007 tome "If I Did It: Confessions of a Killer," but his first contribution to the canon was "I Want to Tell You," which came out on Jan. 7, 1995, when the trial was barely underway.

The book purportedly comprised the defendant's answers to the thousands of letters he'd received since going to jail, an attempt to get ahead of the picture the prosecution planned to paint of a vicious abuser who had finally made good on all his threats. It sold more than 650,000 copies.

Ripped from the headlines

Twenty-one years before the Simpson saga got the slick, Emmy-winning treatment in "The People v O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story" and Ezra Edelman won an Oscar for the epic documentary "O.J.: Made in America, The O.J. Simpson Story," starring Bobby Hosea and Jessica Tuck, which was mainly about O.J. and Brown's volatile relationship, was rushed to Fox.

The New York Times called it "not a movie the defense team would want the jury to see" and an accidental counterbalance to Simpson's "self-serving" book.

Fox made a point of not airing the TV movie until the jury had been sequestered.

Missing perspective

An over-confident Marcia Clark didn't put Jill Shively, who told a grand jury that she saw Simpson, in his white Bronco, speeding down Bundy shortly after 10:45 on the night of the murders, on the stand during the trial. Moreover, Clark instructed the grand jury to dismiss Shively's testimony, saying she couldn't in good conscience have them consider information she didn't have full faith in.

Clark was actually pissed that Shively had sat down with Hard Copy before she was due to give testimony, and the prosecutor figured she had plenty of other witnesses and evidence to nail Simpson with. Who needed one more connecting him to the location in a time frame that fit the crime?

Facts vs. Fiction

Simpson bombed a lie detector test defense attorney Robert Shapiro arranged for him to take, registering a minus-24, according to "The Run of His Life." Polygraph results aren't admissible in court, but can play a role in directing the course of an investigation — and in helping defense attorneys determine the best strategy.

Alan Dershowitz, who mainly advised the defense team from across the country while teaching at Harvard, told the New York Daily News in 2016, when FX's "The People v. O.J. Simpson" had everybody talking, that the fact the polygraph test results went public suggested there may have been a violation of attorney-client privilege.

"There were only four in the world who knew about the lie-detector test," Dershowitz said. "I was not one of them. The four people were Robert Kardashian, who died, Bob Shapiro, O.J. Simpson and the man who conducted the lie-detector test."

However, maybe there were more.

Defense team member F. Lee Bailey, no big fan of Shapiro then or now, told Huffington Post's Highline in 2019 about his co-counsel, "He f--ked up the case on day one by giving O.J. a polygraph test that was totally impossible. You never give those under the circumstances, and he called me immediately saying, 'What do I do next?' And I said, 'Well, first you stop being an a--hole. You call before you give the polygraph test, for Christ's sake!' I saw the charts before he tore them up, and they were nothing but junk." (Shapiro did not comment on Bailey's remarks.)

Search for an accomplice

The prosecution was convinced that Simpson didn't pull it off alone, TIME later reported, and they assigned officers to keep an eye on Simpson's childhood friend and confidante Al Cowlings and Simpson's grown son Jason, from his first marriage, but never gathered evidence that proved the defendant had an accomplice.

Cost of living

After leading police on a 50-mile chase that traversed multiple L.A. freeways, Simpson in the backseat and Cowlings behind the wheel of the former football star's white Ford Bronco, Simpson surrendered at his home and was taken into custody on June 17, 1994. He remained jailed without bail for the duration of the trial. The time he spent on suicide watch cost taxpayers $81,000, after which the price of incarceration averaged out to $55.69 a day.

According to the L.A. County auditor's office, the case cost the city about $800,000 a month.

Front seat driver

Before Marcia Clark invited Christopher Darden onto her team, he was in charge of investigating Cowlings, who was initially arrested on suspicion of aiding a fugitive. The DA's office ultimately opted not to charge him, citing a lack of evidence.

The dream team

Though some drew more attention than others and half of them didn't speak in court, there were at least 10 lawyers who worked on Simpson's case: civil rights activist Johnnie Cochran; Robert Shapiro; F. Lee Bailey; DNA experts and founders of The Innocence Project Barry Scheck and Peter Neufeld; Cochran's associates Carl Douglas and Shawn Holley; Simpson's longtime friend Robert Kardashian; Gerald Uelmen, then the dean of Santa Clara University's law school; and Alan Dershowitz.

Kardashian died of esophageal cancer in 2003, and Cochran died of brain cancer in 2005. Shapiro steered his practice into civil litigation after the trial and co-founded Legal Zoom; he started the Brent Shapiro Foundation for drug abuse awareness after his son died of an overdose in 2005. Douglas and Holley are still practicing trial attorneys who have represented a slew of celebrity clients.

Uelmen was appointed executive director of the California Commission on the Fair Administration of Justice in 2006. Scheck and Neufeld teach at Yeshiva University's Cardozo School of Law. Bailey, later disbarred in the states of Florida and Massachusetts, died in 2021. Dershowitz retired from teaching in 2013 and made recent headlines as a former lawyer for Jeffrey Epstein and as an outspoken critic of the investigation into whether President Donald Trump colluded with Russia (which he insisted was not a defense of Trump but a defense of due process and civil liberties).

The world's most famous houseguest

Brian "Kato" Kaelin, an aspiring actor who was staying in Simpson's guest house, initially moved into Brown Simpson's guest house in January 1993, a month after meeting her in Aspen. He planned on moving into the Bundy condo to help take care of the kids, he testified, but moved onto O.J.'s property instead because he didn't want Kaelin hanging around his ex-wife so much.

Kaelin testified that, on June 12, Simpson returned from daughter Sydney's dance recital and told him that Brown Simpson was preventing him from spending time with Sydney, and he complained that the dress Brown Simpson wore that night was too tight. He and Simpson went to McDonald's and got back at about 9:40 p.m., Kaelin remembered.

Then, at around 10:45 p.m., he heard three loud thumps against his wall. Kaelin went outside but didn't see anything other than a limo waiting. The driver, Allan Park, testified that he saw Simpson go into the house at 10:55 p.m.

Simpson came out at 11 p.m. and Kaelin helped him load his luggage into the limo, except for a backpack Simpson insisted on putting in the trunk himself, Kaelin testified. Park drove Simpson to LAX, where he had an 11:45 p.m. flight to Chicago. (He returned to L.A. on a 12:10 p.m. flight the next day.)

"I had a radio show and there would be constant death threats to me," Kaelin later said on OWN's Where Are They Now? "There'd be faxes [saying] 'Kato should be killed.'

Talking to Barbara Walters in 2015, Kaelin concluded about his old friend, "In my opinion, yes, I think he's guilty."

Man's best friend

Kato Kaelin was close enough to the family that Justin and Sydney Simpson named their dog Kato—and it was Kato the Akita's frantic barks that drew a neighbor, who was out walking his dog, toward Brown Simpson's house at around 10:15 p.m. Not knowing who the Akita belonged to, the neighbor took it home with him, figuring he and his wife could keep it for the night before searching for his owner.

But Kato seemed so nervous, the couple took him outside and the dog led them back to Brown Simpson's house, where they saw that on the path just behind the gate there was a woman lying in a pool of blood.

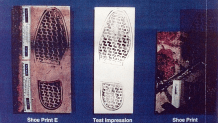

If the shoe fits

Italian shoemaker Bruno Magli got some free publicity when a bloody print at the murder scene was matched to a size-12 Bruno Magli Lorenzo boot.

Simpson denied owning a pair and said later in a deposition for the civil trial that he'd never wear "those ugly ass shoes," but photos were dug up much later showing him wearing the brand on two separate occasions.

"He was very nice," Sam Poser, an associate buyer at Bloomingdale's for men's shoes who testified about showing a pair of Lorenzos to Simpson but couldn't remember if the football star actually bought them, told Footwear News in 2016. "He bought a bunch of dress-casual stuff — he wanted something that was comfortable. But I remembered what he didn't buy more so than I remembered selling him that particular shoe. Eventually, after the criminal trial was over, they found the photograph of O.J. wearing the Bruno Magli shoe at a Bills game. In the civil case, in which I was deposed for, they stipulated that he was indeed wearing those shoes. Had they found that photograph prior to the criminal trial, that could have been a game-changer."

Fixer upper

Defense attorney Carl Douglas later told Dateline that his team switched up some of the decor in Simpson's Rockingham Avenue home before the jury toured it to make it seem as if the tarnished football hero was more in touch with his cultural roots than he really was. Out went a half-naked picture of girlfriend Paula Barbieri, in came African art and a photo of Simpson's mother.

Deputy District Attorney Cheri Lewis had argued that it would be inappropriate for jurors to see sentimental tokens in Simpson's home, such as photos of him with his kids or his trophy room full of memorabilia from his glory days playing for USC and the Buffalo Bills. Especially, Lewis stressed, since Brown Simpson's condo had been stripped of furniture, mementos and anything else that made it personal and warm, a place she had lived with her children.

The tour of the Bundy crime scene included Simpson's house to help the jury get a sense of the distance between the two locations and whether or not Simpson could have killed the ex-wife and Goldman, then have returned to his place in time to get in a car with limo driver Allan Park and catch his 11:45 p.m. flight to Chicago.

Remote control

Dershowitz made some appearances in court but mainly served as a member of Simpson's defense team from afar while busy with his day job, teaching at Harvard Law School. During the trial, he simultaneously watched CNN and Court TV, which was televising all of it, and would fax his fellow attorneys memos in real time that they could read right there in the courtroom.

''This is the first trial of the 21st century in some respects,'' he told the Christian Science Monitor in February 1995. ''Having a lawyer outside the courtroom monitoring the case who has quick access to research is the wave of the future. I think more big law firms with complex litigation are going to move to this model."

Candid camera

Judge Lance Ito considered pulling the plug on the cameras televising the trial (he prevented them from broadcasting the gory crime scene photos), but the defense was on the side of the public having the right to see the whole story play out and, as many remember, the proceedings turned into must-see TV.

At the same time, Ito was very conscious (and concerned) about his own press, and he delighted in the celebrity attention he got, such as in the form of The Tonight Show With Jay Leno's recurring bit featuring the "Dancing Itos."

"He had thought it was great and loved it and wanted all of us to see it in chambers," Peter Neufeld later told TIME. "You may find that amusing on a personal level, but I can assure you that on a professional level it is so unacceptable, for a judge who is presiding over a murder where two people lost their lives in the most gruesome and horrible fashion, and where a third person has his life on the line, to bring the lawyers into chambers to show them comic revues."

The race card

Chris Darden tried to argue that the jury shouldn't be allowed to hear the recording of Mark Fuhrman using the n-word because it would upset the Black jurors (who made up a majority on the panel) too much and therefore prove prejudicial against Fuhrman.

"If you allow Mr. Cochran to use this word and play the race card," he said, "the direction and focus of the case changes: it is a race case now."

Johnnie Cochran wasn't having it.

"I am ashamed that Mr. Darden would allow himself to become an apologist for this man," the seasoned activist and litigator said, among other things, in castigating opposing counsel. After which, Cochran hugged Simpson and left for a funeral.

"First of all, I had told Darden not to take Fuhrman," Cochran recalled to TIME in 2001. "But I was really disappointed with him. He came into the judge's chamber with a copy of Andrew Hacker's book, Two Nations. He gives Ito one of these things. I can't believe he's doing this. And basically, he's saying, if you allow these jurors to hear the word it's the most vile word in the dictionary; it'll turn this trial into whether these jurors believe that the brothers on the street think 'the man' is getting a fair trial. My first reaction was to say to Darden, 'N---er, please...'"

"I was so furious with him," the attorney continued. "I felt it was an insult to all Black people. When I got up and spoke, that was not scripted. That was just from my heart."

The glove debacle

The infamous extra-large leather gloves, one found at the crime scene, the other behind Simpson's house, made for a matching set and were like a pair Brown Simpson had bought for her then-husband in 1990 at Bloomingdale's. Only 200 pairs were sold in the whole country that year.

A trace of Goldman's DNA was on the glove found at Rockingham and fibers on that glove matched carpeting in Simpson's Bronco. Traces of O.J's, Brown Simpson's and Goldman's blood were all found in the Bronco. Also, a sock with drops of both O.J.'s and Brown Simpson's blood on it was found in his bedroom.

Simpson said he must have left his blood behind at Bundy some time when he was over there playing with his kids. The story of how and when he cut his finger kept changing, at first saying it happened in Chicago, but then he said it happened in L.A. and he reopened the cut in Chicago.

When Simpson tried on the gloves in court, at Darden's insistence and much to Clark's dismay and the defense's amusement, he raised his hands and declared, "They don't fit."

"If it doesn't fit, you must acquit," Cochran said in what became perhaps the most quoted — everyone can remember a rhyme — statement of the entire trial. One, incidentally, that Gerald Uelmen suggested, though Cochran's delivery was key.

"But what I was really proposing was that it would provide a good theme for the whole argument," Uelmen told TIME, "because so much of the other circumstantial evidence didn't fit into the prosecution's scenario."

Glove Slap

It ended up providing one of the most memorable moments of the whole trial and a real coup for the defense, but in a pretrial hearing Simpson's lawyers initially tried to get the glove found at Rockingham thrown out, citing unwarranted search and seizure, a violation of Simpson's Fourth Amendment rights.

"I thought we presented a very compelling case that the glove should have been suppressed," Uelmen said on Frontline in 2005. And the ironic thing is that if the judge had granted that motion and thrown out the glove, I think the result in the Simpson case would have been different. Mark Fuhrman would have been out of the case. They had a pretty compelling case without the glove. The glove kind of opened the door to all of the questions about Mark Fuhrman's credibility and his racism. And when he then became such an important witness in the trial, that then opened the door to all of the problems that Mark Fuhrman created for their case.

"So ironically, if the judge had followed the law, and I think the law really required her to suppress that evidence."

Ultimately, he said, "I thought we presented a very compelling case of reasonable doubt, and we had a great jury."

Under Attack

While Marcia Clark, a part of the L.A. County District Attorney's Office's special trials unit since 1989, was trying to prosecute Simpson for murder, she was also constantly put on the defensive. Her style was criticized, so she got a new hairdo and was criticized for that. Her ex-husband sued her for primary custody of their two sons during the trial, alleging she was working too much to properly take care of them. The National Enquirer published old topless photos of her taken on a vacation with her then-husband. Even a potential juror, a woman, when asked if there was anything she might hold against the prosecution, told Clark, "I think your skirts are too short, how about that?"

She was dismissed. But not before Judge Ito cracked, "I was wondering when someone was going to mention that."

But the families of the victims she was trying to get justice for had the utmost confidence in her, at least heading into the trial.

"She seems always to be concerned with our family, how we're doing, and at the same time there's never a doubt in my mind she's working 25 hours a day, 10 days a week, on this case," Fred Goldman, Ron's father, told the New York Times. "On a scale of 1 to 100, she easily gets 110."

Brown Simpson's sister Denise Brown told The New Yorker, "I think Marcia is wonderful, a terrific woman, and I think my whole family will vouch for that one."

Reasonable Doubt

Aside from suggesting that detectives tried to frame Simpson, the defense proposed the theory that the murders were drug-related, committed by dealers who came to the house looking for Brown Simpson's friend and — up until the day before the murders — house guest Faye Resnick, an interior decorator who later became a familiar face on "The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills."

Resnick co-wrote a couple of books stemming from the case, starting with "Nicole Brown Simpson: The Private Diary of a Life Interrupted," which came out in 1994, right in the middle of jury selection. Thanks to all the salacious details she included about Brown Simpson's purported sex life, Resnick became only a questionably helpful witness for the prosecution, despite her firm belief that Simpson had battered Brown Simpson through the course of their relationship and ultimately killed her.

"Shattered: In the Eye of the Storm," about how the trial affected Resnick, came out in 1996.

Battered Reputation

Bob Shapiro brought F. Lee Bailey on board for his extensive murder trial experience, of which Shapiro — a criminal defense attorney more inclined to cut deals — had none. Bailey was best known for defending Albert DeSalvo, who later confessed to being the "Boston Strangler" serial killer, on assault charges and heiress Patty Hearst when she went on trial for helping her kidnappers rob a bank. (Both convictions.)

Some of Bailey's key moments during the Simpson trial included him goading Darden into having O.J. try on the gloves in court and his cross-examination of Fuhrman.

After Simpson was acquitted, Bailey said on CNN that Shapiro initially wanted Simpson to plead guilty to manslaughter — a charge Shapiro denied, though it was widely reported that conversations about a possible plea were held at his office.

"We tried to fire Shapiro for being an a--hole," Bailey told Huffington Post's Highline in 2019. "O.J. told him, 'You're benched,' and Bob said, Fine. I'm going out to give the public my opinion of your guilt.' O.J. knew that would be devastating before the trial, so we kept Bob aboard."

Bailey was later disbarred in Florida and Massachusetts and set up a consulting firm in Maine, but wasn't able to acquire a license to practice law.

He told the ABA Journal in 2014 he believed his work on the case "hurt in Florida, Massachusetts and in Maine. There has been a strong wave of judicial resentment against me for my role in the O.J. Simpson trial."

Repercussions

Under cross-examination by Bailey, Fuhrman denied having ever having used the n-word, a statement that was handily proved untrue by the defense, which had a recording of him using the epithet in conversations he had with an aspiring screenwriter. Without the jury present, the detective then asserted his Fifth Amendment right not to incriminate himself when asked whether he had planted or manufactured evidence in the Simpson case.

In a memorandum obtained by the New York Times, Dershowitz had puzzled over why the prosecution felt the need to have Fuhrman testify, since he had only spotted the glove at Simpson's and pointed it out to fellow detectives. He wasn't the one who physically removed it from the scene and checked it into evidence, therefore he wasn't part of the chain of custody.

Before the trial concluded, Fuhrman, a 20-year veteran of the LAPD, had retired. He pleaded no contest to perjury in 1996 and in 1997 he released "Murder in Brentwood," about the Simpson case, the first in a number of books he's since written about true crime, media and the justice system. He moved to Idaho and became a regular guest on Fox News

Throughout, Fuhrman has maintained that he went by the book in the Simpson case and the evidence proved his guilt. He told the New York Post in 2016, "There will be another Simpson, and what we have learned is that political correctness and stupidity trump justice."

Alternate Takes

Over the course of the trial, 10 out of the 27 people seated — 12 jurors and 15 alternates — were dismissed for various reasons. Only four of the original main jurors were left to decide the verdict.

Lionel Cryer was originally selected as an alternate but ended up ascending to the main panel. "I was not excited," he told E! News in 2017. "I looked around at all the people I was going to be making this decision with and I thought, this is going to be quite a ride."

In the end, 10 women and two men found Simpson not guilty. Nine of the jurors were Black, two white and one Hispanic.

After he was acquitted, Simpson said finding the real killer would be his "primary goal in life."

Hollow victory

"Sometimes, I turn around and I look at the Goldmans, and if you could see the hurt and suffering on their faces," Chris Darden told the Los Angeles Times during the trial. "Sometimes, I see them, and they're smiling, but when they are in the courtroom, sometimes they are dying inside. The victims just keep mounting up. The Goldmans are victims. The Browns are victims. The Simpsons are victims. Sydney and Justin Simpson are victims. We're victims because the grief and the pain and the suffering are spread around equally."

In one of the justice system's quirkier quirks, despite being found not guilty of murder Simpson was found liable for Ron and Brown Simpson's deaths in a civil trial and was ordered to pay $33.5 million to the Goldman and Brown families.

Which he has not done.

After he was acquitted, Simpson said finding the real killer would be his "primary goal in life."

In what many of Simpson's supporters — and plenty of his detractors, too — figure was a message-sending move, a Nevada judge threw the book at Simpson in 2008 when he was convicted of armed robbery, kidnapping, assault and other charges over a plot to get items he insisted were his back from a memorabilia dealer at a Las Vegas hotel.

Simpson was sentenced to nine to 33 years in prison; he was paroled after nine in 2017 and before his death, he remained in Nevada, golfing and tweeting to his 860,000-plus followers, having joined the site in June 2019.

F. Lee Bailey, who passed away in 2021, told HuffPost's Highline two years earlier he was "frequently" in touch with Simpson. "I'm out in Las Vegas a lot," he said. "He lives a very quiet life there."

(Originally published June 10, 2019, at 3 a.m. PT)