Hundreds of thousands of firearms stolen from the homes and vehicles of legal owners are flowing each year into underground markets, and the numbers are rising. Those weapons often end up in the hands of people prohibited from possessing guns. Many are later used to injure and kill.

A yearlong investigation by The Trace and more than a dozen NBC TV stations identified more than 23,000 stolen firearms recovered by police between 2010 and 2016 — the vast majority connected with crimes. That tally, based on an analysis of police records from hundreds of jurisdictions, includes more than 1,500 carjackings and kidnappings, armed robberies at stores and banks, sexual assaults and murders, and other violent acts committed in cities from coast to coast.

"The impact of gun theft is quite clear," said Frank Occhipinti, deputy chief of the firearms operations division for the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives. "It is devastating our communities."

Thefts from gun stores have commanded much of the media and legislative attention in recent years, spurred by stories about burglars ramming cars through storefronts and carting away duffel bags full of rifles and handguns. But the great majority of guns stolen each year in the United States are taken from everyday owners.

Thieves stole guns from people’s closets and off their coffee tables, police records show. They crawled into unlocked cars and lifted them off seats and out of center consoles. They snatched some right out of the hands of their owners.

In Pensacola, Florida, a group of teenagers breaking into unlocked cars at an apartment complex stole a .22-caliber Ruger handgun from the glovebox of a Ford Fusion, then played a video game to determine who got to keep it. One month later, the winner, an 18-year-old man with an outstanding warrant for his arrest, fatally shot a 75-year-old woman in the back of the head who had paid him to do odd jobs around her house. She had accused the gunman of stealing her credit cards.

U.S. & World

In Gilbert, Arizona, a couple left four shotguns out in their bedroom and two handguns stuffed in their dresser drawers even though they had a large gun safe in the garage. They returned home to find their sliding backdoor pried open and all six of the weapons missing. Police recovered one of the shotguns eight months later on the floor of a getaway car occupied by three robbers who held up a gas station and led officers on a harrowing chase in the nearby city of Chandler.

In Atlanta, a thief broke through a front window of a house and stole an AK-47-style rifle from underneath a mattress. The following year, a convicted felon used the weapon to unleash a hail of bullets on a car as it was leaving a Chevron gas station, sending two men to the hospital. Two months later, the felon used the rifle to fatally shoot his girlfriend’s 29-year-old neighbor. A 7-year-old girl who witnessed the killing told police the crack of the gunfire hurt her ears. She ran home crying to her mother.

After the Las Vegas and Sutherland Springs mass shootings, attention fell on exotic gun accessories and gaps in record keeping. Last week, a new measure intended to shore up the federal background check system was introduced by eight U.S. senators. But many criminals are armed with perfectly lethal weapons funneled into an underground market where background checks would never apply.

In most cases reviewed in detail by the Trace and NBC, the person caught with the weapon was a felon, a juvenile, or was otherwise prohibited under federal or state laws from possessing firearms.

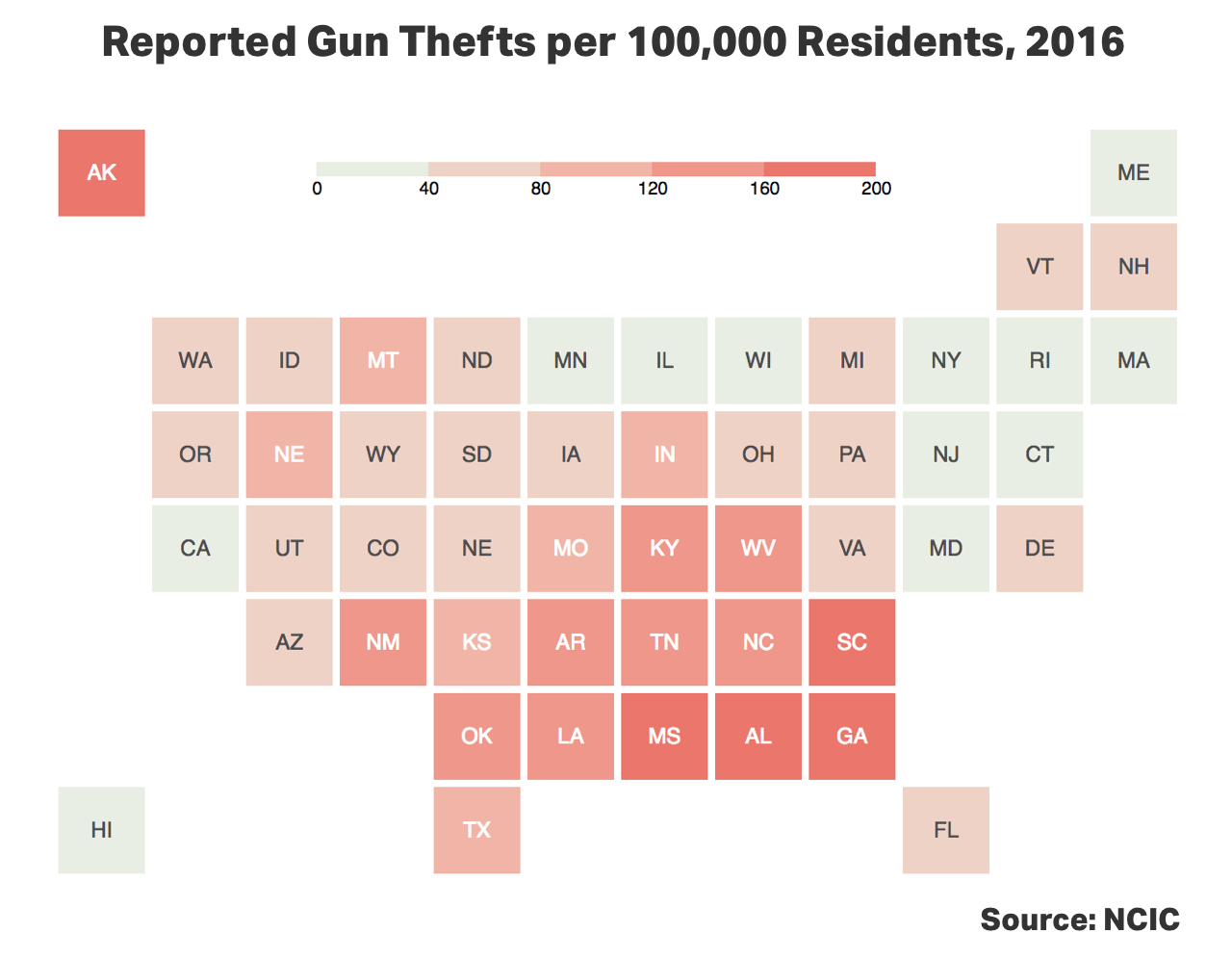

More than 237,000 guns were reported stolen in the United States in 2016, according to previously unreported numbers supplied by the National Crime Information Center, a database maintained by the Federal Bureau of Investigation that helps law enforcement track stolen property. That represents a 68 percent increase from 2005. (When asked if the increase could be partially attributed to a growing number of law enforcement agencies reporting stolen guns, an NCIC spokesperson said only that "participation varies.").

All told, NCIC records show that nearly two million weapons have been reported stolen over the last decade.

The government’s tally, however, likely represents a significant undercount. A report by the Center for American Progress, a left-leaning public policy group, found that a significant percentage of gun thefts are never reported to police. In addition, many gun owners who report thefts do not know the serial numbers on their firearms, data required to input weapons into the NCIC. Studies based on surveys of gun owners estimate that the actual number of firearms stolen each year surpasses 350,000, or more than 3.5 million over a 10-year period.

"There are more guns stolen every year than there are violent crimes committed with firearms," said Larry Keane, senior vice president of the National Shooting Sports Foundation, the trade group that represents firearms manufacturers. "Gun owners should be aware of the issue."

On a local level, gun theft is a public safety threat that police chiefs and sheriffs are struggling to contain. The Trace requested statistics on stolen weapons from the nation’s largest police departments in an effort to understand ground-level trends. Of the 80 police departments that provided at least five years of data, 61 percent recorded per-capita increases in 2015 compared to 2010.

The rate of gun thefts more than doubled in Sioux Falls, South Dakota; Madison, Wisconsin; and Pasadena, California, our analysis found.

More than two-thirds of cities experienced growth in the raw number of stolen-gun reports, not accounting for population change.

There were 843 firearms reported stolen in St. Louis in 2015 — a 27 percent increase in reports over 2010.

"We have a society that has become so gun-centric that the guns people buy for themselves get stolen, go into circulation, and make them less safe," said Sam Dotson, a former St. Louis police chief.

Identifying the precise nexus between stolen firearms and other forms of crime is a question that has flummoxed researchers and journalists for years, in part because of strict legal limits on the public’s access to national data. The ATF is barred under a rider to a Department of Justice appropriations bill from sharing detailed crime gun data, which could include information about whether a weapon was stolen, with anyone outside of law enforcement.

The Trace and NBC sidestepped federal restrictions, in part, by obtaining more than 800,000 records of both stolen and recovered firearms directly from more than 1,000 local and state law enforcement agencies in 36 states. Matching the serial numbers of guns contained in the two sets of records enabled our reporters to identify crimes involving a weapon that had been reported stolen.

The trend is unambiguous: Gun theft is on the rise in many American cities, and many of those stolen weapons are later used to injure and kill people.

A research paper published this year, using responses from the Harvard and Northeastern survey, estimated that three million Americans carry loaded handguns in public every day. About nine million people carried a handgun at some point during the month before the survey was conducted, researchers found. Six percent of respondents who said they carried a gun had been threatened with a firearm in the previous five years.

In the past two decades, dozens of states have passed legislation easing restrictions against carrying in public. Some, like Georgia, have made it possible to legally carry a concealed weapon in restaurants and churches. At least a dozen, including Missouri, Arizona, and West Virginia, have done away with all training or licensing requirements, meaning anyone legally allowed to own a gun can carry it concealed in public.

People who owned guns for protection or carried a gun in the previous month were more than three times as likely to have experienced a theft in the previous five years, according to a study published this year that was based on the Harvard and Northeastern survey results. People who owned six or more guns and stored their guns loaded or unlocked — or kept guns in their vehicles — were more than twice as likely to have had their firearms stolen.

In Texas, gun owners have reported thousands of thefts. Austin alone tallied more than 4,600 reports of lost or stolen guns between 2010 and 2015, more than 1,600 of which were swiped from cars, The Trace and NBC found. Over that same period in Austin, lost and stolen guns were recovered in connection to at least 600 criminal offenses, including more than 60 robberies, assaults, and murders.

Many gun-rights advocates, including Jerry Patterson, a former Texas state senator, believe that owners have a responsibility to guard their weapons from theft.

"You’re negligent if you don’t exercise good judgment," he said. "There’s too many guns in the hands of dumbasses that don’t know how to use it, don’t know how to store it."

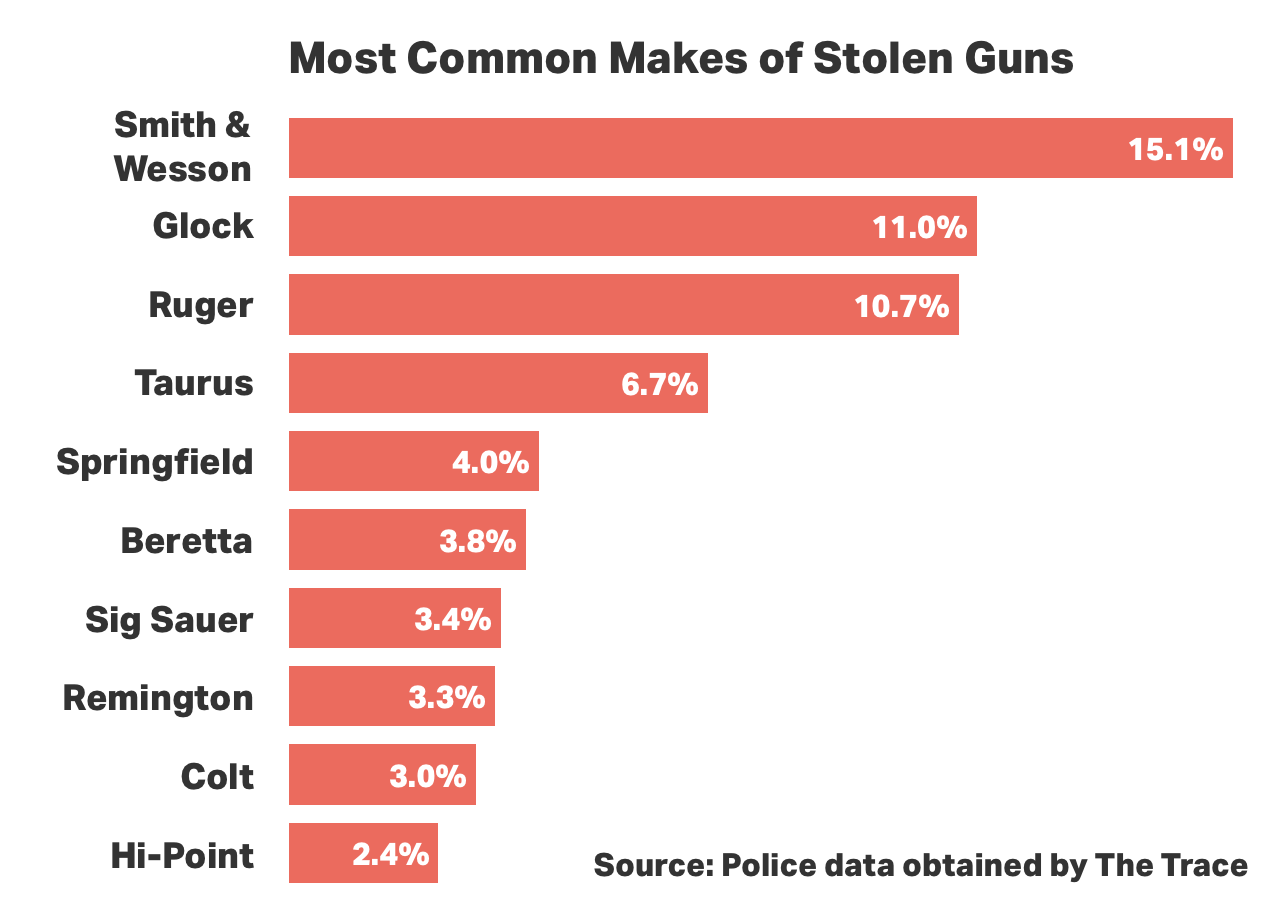

In Houston about a decade ago, someone broke into Patterson’s truck, making off with a Smith & Wesson .357 revolver. "Now I don’t leave handguns in the car," he said.

Instead, Patterson now keeps a shotgun under the back seat.

"It’s harder to steal a long gun discreetly," he said.

The International Association of Chiefs of Police recently tasked a team of top of law enforcement officials to develop a program that police officers and sheriff’s deputies can use to press gun owners into safeguarding their weapons. At the organization’s annual conference in Philadelphia in October, the team premiered a public service announcement that showed a burglar stealing a gun from an unlocked car and then embarking on a robbery spree.

"We leave our cell phones in our cars, and we go crazy. But you leave your firearm and it’s like we forget," said Armando Guzman, a chief of police from Florida who was one of the principal architects of the prevention effort. "Look at the consequences."

Most states don’t require gun owners who leave weapons in a car or truck to secure them against theft. Kentucky’s law specifically says that owners may keep firearms in a glove compartment, center console, seat pocket, or any other storage space or compartment regardless of whether it is "locked, unlocked, or does not have a locking mechanism."

Homes are generally a more secure place to store firearms, but even indoors, guns can be a magnet for thieves.

Researchers at Duke University and The Brookings Institution found in 2002 that thieves were more likely to break into homes in areas where gun ownership rates were high. The researchers concluded that instead of being a deterrent to crime, guns enticed thieves looking for a lucrative score.

In a large share of the burglaries in which a gun was stolen, it appeared that was the only item taken, suggesting that the thief knew the house had a gun in it and went after it, said Philip Cook, a professor at Duke who co-authored the study.

"That’s why people who put up signs that say, ‘This house is protected by Smith & Wesson,’ are taking a chance, just like people who put NRA stickers on their cars are taking a chance," Cook said. "It signals that this might be worth breaking into."

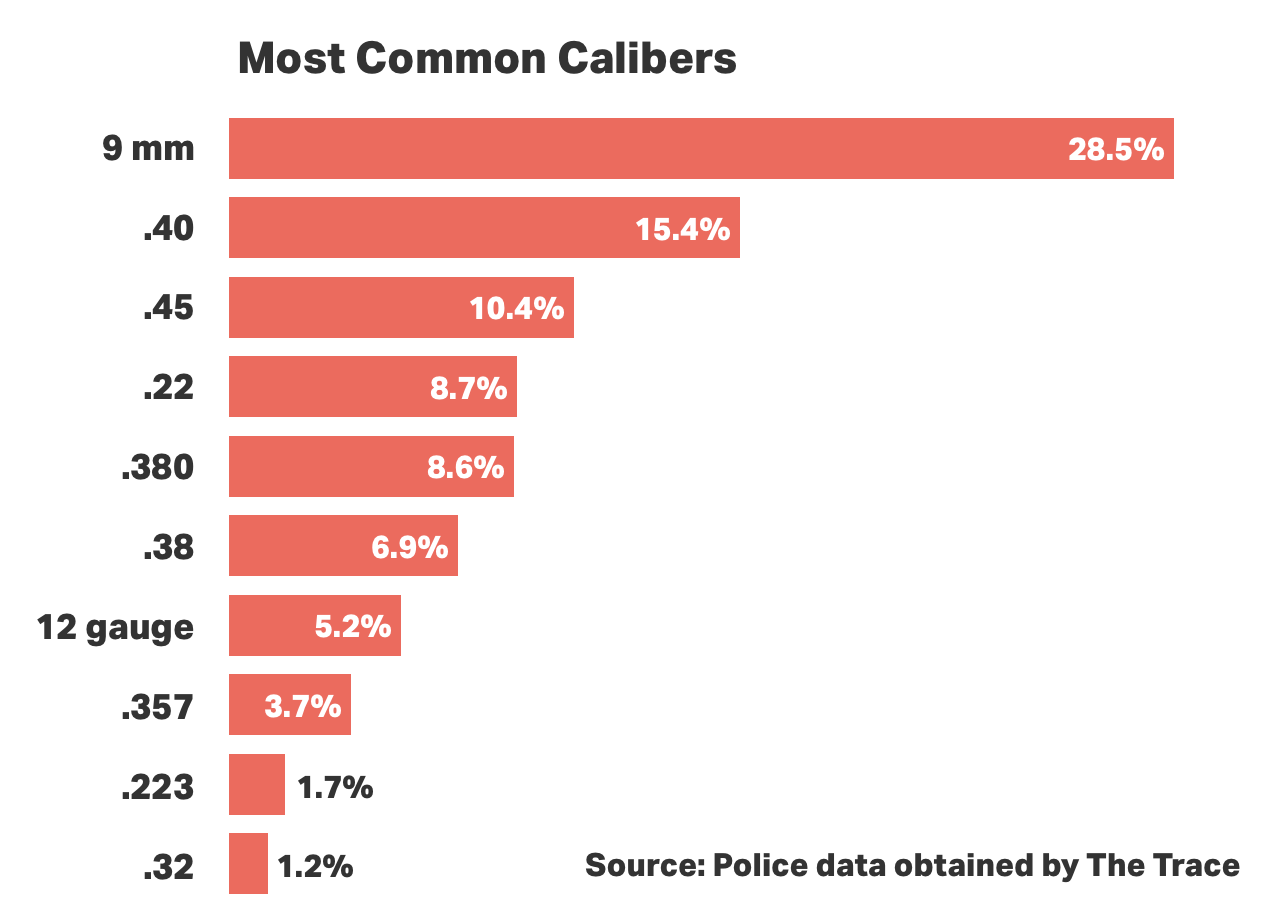

Of the nearly 150,000 records of stolen weapons analyzed by The Trace and NBC in which the type of gun was listed, 77 percent were handguns.

Law enforcement officials and researchers say that stolen guns are usually sold or traded for drugs. "Guns are the hottest commodity out there, except for maybe cold, hard cash," said Kevin O’Keefe, the chief of the ATF’s intelligence division. "This is a serious issue."

Most stolen guns were recovered within the same city or state as the scene of the theft, sometimes years or even decades later, The Trace and NBC found.

The Trace and NBC identified more than 500 guns that were stolen and then crossed state lines, sometimes traveling hundreds or even thousands of miles, before turning up at the scene of a crime. Many of those guns followed trafficking routes that are well known to law enforcement, flowing from states with looser laws to states with stricter ones.

[[458850633, 245, 330, L]]

A Smith & Wesson stolen from an unlocked pickup truck in Florida was recovered in connection to a shooting in Camden, New Jersey. A revolver stolen in Hampstead, New Hampshire, found its way to Boston, where police stopped a gunman at a high school graduation. A .380-caliber Jimenez pistol stolen from a house in Hammond, Indiana, came into the possession of an 18-year-old gang member in Chicago, who tossed it onto a front porch while he was running from police.

In South Carolina, a former state trooper reported his .40-caliber Glock stolen from his unlocked pickup in 2008. The gun was recovered during a drug arrest and the former trooper got it back, only to have it stolen from his truck again in 2011. Four years later, New York Police Officer Randolph Holder, 33, was responding to reports of a shooting in East Harlem when he encountered Tyrone Howard, a 30-year-old felon who had been in and out jail since he was at least 13. Howard pulled out the stolen Glock pistol and fatally shot Holder in the head.

Few states require gun owners to report theft

When a gun store is burglarized, it must report any missing firearms. Under federal law, licensed firearms dealers have to maintain records — including the make, model, and serial number of each gun in their inventory — and provide them to investigators so they can attempt to recover the weapons.

[[458855413, 245, 365, L]]

Everyday gun owners are not held to the same record keeping requirements. Only 11 states and the District of Columbia have a version of a law that requires gun owners to report the loss or theft of a firearm to police. Law enforcement officials say stolen-gun reports help them spot trends, deploy resources, and get illegal weapons off the street.

Keane, the National Shooting Sports Foundation’s senior vice president, said that while gun owners should lock up their weapons when they’re not in use, he opposes penalizing gun owners who don’t report a theft. "The focus has to be on criminals," he said. "If they’re using stolen firearms then there should be severe consequences from that."

Law enforcement experts and advocates of gun-violence prevention say that the attention should be on preventing thefts from happening in the first place.

Massachusetts is the only state where gun owners must always store firearms under lock and key, according to the Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence. California, Connecticut, and New York require guns to be locked in a safe or with a locking device in certain situations, including when the owner lives with a convicted felon or domestic abuser.

All four states experience theft rates well below the national average, according to NCIC data.

"There ought to be some obligation in the law for gun owners to responsibly secure their firearms," said Sen. Richard Blumenthal, a Connecticut Democrat. "Congress should not only be looking at this issue, they ought to be acting on this issue."

— Daniel Nass, Max Siegelbaum, Miles Kohrman, Mike Spies of The Trace contributed to this story.