Brooke Rusenko woke up the morning after the 2016 presidential election and, distraught, felt she hadn’t done enough to stop Donald Trump from winning.

She resolved that from that point forward, she’d show up. Last week, Rusenko, a part-time lawyer, flew from her home in Northern California to volunteer for Kamala Harris’ campaign in the crucial suburban counties that ring Philadelphia.

She has joined volunteers from all over the U.S. and overseas who have descended on a bustling field office in the storied Main Line suburbs west of the city. They left jobs and families behind to knock on doors, make phone calls, fold and package literature — anything to improve Harris’ chances even to the slightest degree.

“Waking up when Donald Trump won the election was one of the worst feelings I had in my whole life,” Rusenko, 41, said in an interview with NBC News. “I had wished I had done more, and I hadn’t. I felt I had let myself down by not working harder, and I’ve vowed not let that happen again.”

The work is grinding, rejection a constant companion. Only a fraction of people knocking on doors actually reach someone inside. Harris’ campaign isn’t only targeting Democrats who might need a gentle reminder to show up and vote, but also an elusive niche of the electorate: Republicans who’ve grown disillusioned with Trump.

Interviews with two dozen campaign aides, Democratic strategists, volunteers and elected officials suggest that Harris’ hopes in Pennsylvania hinge on a ground operation that they believe dwarfs anything Trump has assembled.

U.S. & World

“We have 50 offices across the commonwealth and over 450 paid staff, thousands upon thousands of volunteers, and we’re knocking on doors at a rate that Donald could never dream of matching,” said Brendan McPhillips, a Harris campaign adviser in Pennsylvania.

Last week, NBC News asked if the Trump campaign would let a reporter come see one of its field offices in the Philadelphia suburbs. In response, a Pennsylvania-based Trump official extended an invitation to a get-out-the-vote event in Philadelphia on Saturday, but later phoned to say it had been called off.

Get a weekly recap of the latest San Francisco Bay Area housing news. >Sign up for NBC Bay Area’s Housing Deconstructed newsletter.

As for Harris, volunteer and paid staff are searching for the sorts of voters who backed former South Carolina Gov. Nikki Haley in the GOP primary in April and now may want Harris to win.

That takes time and persistence. But the Harris campaign believes it has marshaled enough people to saturate this patch of Pennsylvania, find these voters and turn them out in numbers that could be decisive in a tight race. It’s the ground game version of “shock and awe.”

Describing the voter contact effort in Pennsylvania, McPhillips said: “We’re putting up insane numbers.”

“We can have tens of thousands of conversations a day, and considering that the margin of President Biden’s win in 2020 [in Pennsylvania] was like 80,500 votes, we’re talking to a big chunk of that margin every day at this point.”

‘Nikki Haley voters are gettable’

The Harris office in Wayne is one of 11 in the four suburban counties that are, once again, the epicenter of a ferocious fight to capture Pennsylvania.

Democrats have spent months building a get-out-the-vote apparatus here and are betting that, in the end, they will outperform what the Trump campaign official described as the former president’s comparatively “lean operation” in the state.

Onetime Haley voters may be the biggest prize.

In the suburbs, about 42,000 people chose Haley over Trump in the Pennsylvania GOP primary, even though she had dropped out of the race more than a month before.

That’s a large trove of votes in a race that is now deadlocked. When Trump last won Pennsylvania in 2016, his victory margin was only about 44,000 votes.

“These are people we still think are persuadable. So, we’re still working on these voters,” said state Sen. Maria Collett, a Democrat who represents the suburbs.

Harris has enlisted anti-Trump Republicans to vouch for her and make the case to GOP voters who may have soured on Trump. One is Jim Greenwood, a former moderate Republican congressman who represented Bucks County in Congress for 12 years.

Another is Liz Cheney, the former Wyoming congresswoman who lost her seat after breaking with Trump. The daughter of former Vice President Dick Cheney, she appeared with Harris last week at an event in Chester County, in hopes of reaching Republican voters who are open to splitting their ticket.

“We know the Nikki Haley voters are gettable — not all of them, but probably a large percentage,” McPhillips said.

Joseph Hoeffel is a former Democratic congressman who represented Montgomery County, the third largest in Pennsylvania. He said he couldn’t have gotten elected over the years had it not been for Republicans willing to split their ticket, and he expects these independent-minded voters will do the same for Harris.

“In my experience, Montgomery County has been the home of ticket-splitting Republicans,” said Hoeffel, who has been going door to door for Harris’ campaign. “There’s still a Nikki Haley branch of the Republican Party, and that is clearly what Harris is smart enough to go after. There are a lot of Haley Republicans in Montgomery County, and I bet most of them will very quietly, but very surely vote for Harris.”

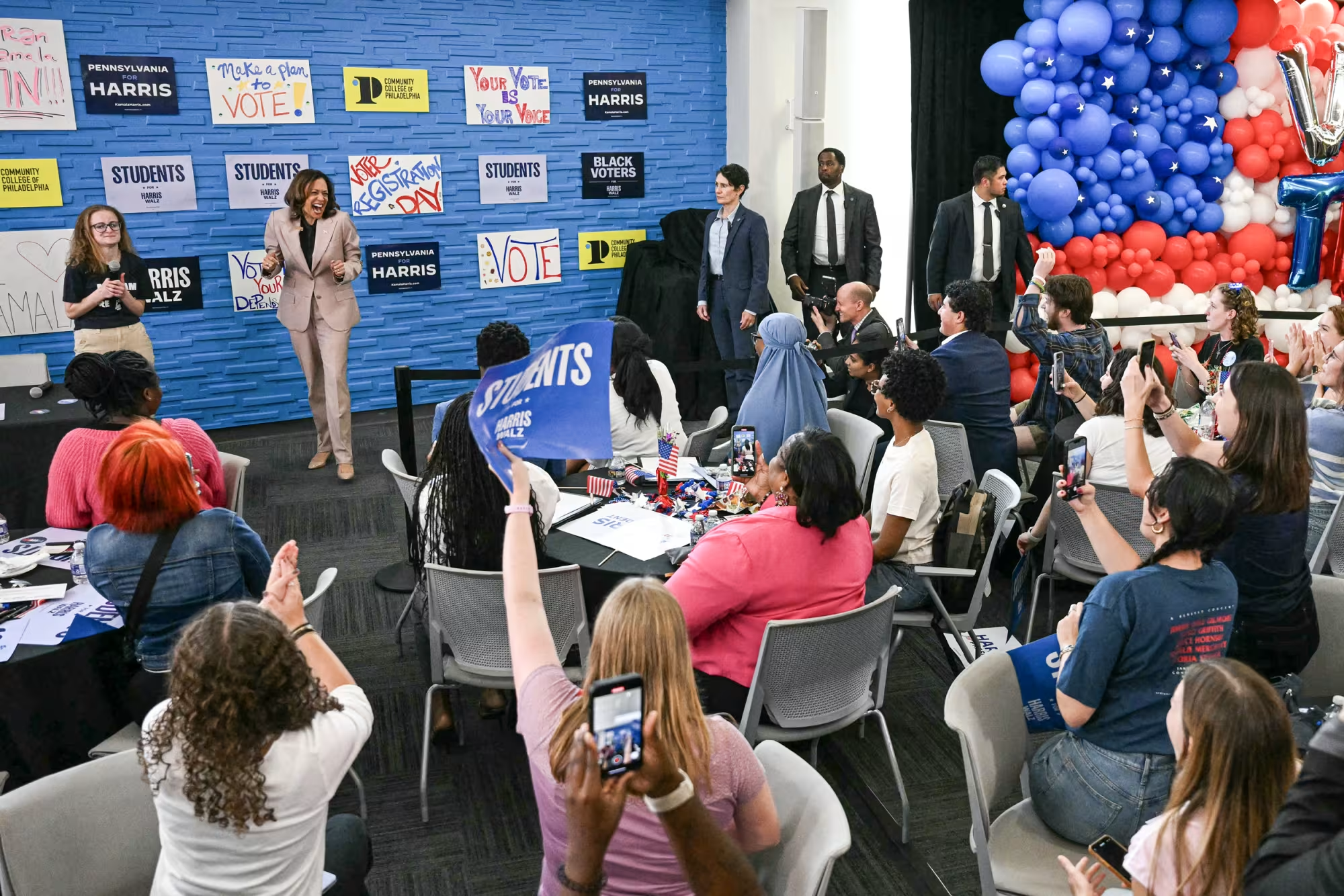

Both Harris and Trump are making frequent visits to the suburbs as Election Day nears, a measure of the region’s outsize importance. Trump chose Bucks County for his recent photo-op working the fryer at a local McDonald’s restaurant. Harris’ town-hall-style event on CNN last week took place in Delaware County.

A dizzying number of possibilities could tip the result in Pennsylvania one way or the other. Even if Harris performs well in the suburbs, can she count on the Democratic stronghold of Philadelphia to turn out in the numbers needed to win? It’s tough to predict.

Bob Brady, chairman of the city Democratic Party and a longtime Philadelphia power broker, said he expects that Harris will attract more Black votes than Biden would have won had he stayed in the race. But he also said Harris won’t do as well as Biden in largely white precincts in northeast and south Philadelphia.

Hosting a pizza party for Philadelphia ward leaders last week, Brady said in an interview, “I’ve got friends, a couple of them will be here today, and they’re for Trump. You can’t talk to them. He’s got that 47% of zealots. It’s scary as hell.”

A kerfuffle between the city’s Democratic leadership and the Harris campaign could complicate the outcome. A Philadelphia tradition is to pay “street money” to Democratic foot soldiers who help turn out the vote in presidential elections. The Harris campaign committed to pay $100 apiece to the 3,500 city Democratic committee members involved in get-out-the-vote efforts, a city party official said, but Philadelphia Democrats are asking for more money.

If they get it, Brady said the money would help pay more people to canvass neighborhoods and get voters to the polls.

“They [the Harris campaign] didn’t give us enough,” Brady said. “Someone is telling them not to give it to us. I don’t know who, but they’re making a major mistake.”

A Harris campaign official said in response: “Of course Bob Brady loves the idea, because they use the money to pay committee people to stand at the polls on Election Day.”

While “people need that check, that’s not a major piece to how we win a campaign and that’s why we aren’t giving him everything he wants,” the official added.

‘Excitement, dread and tension’

No one looking for a respite from the election should venture anywhere near the Philly suburbs. A dog who cheerfully greeted customers at a men’s clothing store in Wayne wore a little Harris-Walz sweater.

A random conversation at a table in a local Italian restaurant included a snippet about ticket-splitting: “Trump could very well win Pennsylvania and Casey could also win.” (Sen. Bob Casey, a Pennsylvania Democrat, is up for re-election this year.)

Trump and Harris signs pop up everywhere — at least the ones that haven’t been stolen. Harris supporters say thieves have been showing up at night and running off with yard signs. Owners have tried different deterrents, even posting notes on the signs saying that if any are taken, they’ll give a $100 donation to Harris’ campaign. But the vandalism has continued. A bunch of Harris signs were found strewn in a ditch in Montgomery County.

When he canvasses neighborhoods and speaks to voters, Hoeffel said he hears the same plaintive plea within the first few seconds: “They want the election to be over!”

Yet there’s also a blend of excitement, dread and tension about a race that has taken dark turns. Neil Makhija, a Montgomery County commissioner and chairman of the local board of elections, said he’s gotten complaints from residents who’ve felt intimidated by people lurking around ballot drop boxes, recording them as they deposit their envelopes. He said he’s forwarded the complaints to the district attorney’s office.

Local officials are also bracing for a slew of postelection challenges to the results. Josh Maxwell, chairman of Chester County’s board of commissioners, said the county has already received more than 200 challenges to mail-in ballot applications — a number he said is unusually high. The challenges center on people who have requested mail-in ballots in Pennsylvania, but who also have addresses outside the state.

“Having a second home in Florida doesn’t prevent you from voting in Pennsylvania,” Maxwell said in an interview.

The challenges, he added, will need to be adjudicated and add “another layer of undue suspicion at a time when people absolutely don’t want it.”

‘Shiny toys’

Both sides expect the result in Pennsylvania to be tight. As of Friday, Democrats have returned ballots in numbers exceeding Republicans in Philadelphia and each of the four counties, though that does not necessarily correlate to votes for Harris or Trump. And Democrats have historically outperformed Republicans in early voting volume.

The election will test the potency of two disparate campaign models. Democrats are relying on Harris, but also on field work ensuring that voters actually vote. In the last week, the Harris campaign says that it has knocked on 235,000 doors in the suburban counties alone.

Trump’s model is largely built around his persona and the emotional connection he has forged with his base. His ground game appears to be more modest, targeting “low-propensity voters” who may not be following the election closely though they lean toward Trump. The Trump campaign official said that the campaign has opened a total of four offices in the suburbs.

But the Trump official said that bigger isn’t necessarily better, pointing to state voter registration trends. Between 2021 and 2024, thanks in part to a change in state law that automatically registered more voters, the Democrats’ voter registration advantage in Pennsylvania was cut in half and now stands at about 300,000.

Referring to the Harris campaign’s $1 billion fundraising haul, the Trump official added: “They have a lot of shiny toys on their side. They have a billion dollars to blow; they should have a lot of shiny toys. But unless the shiny toys are doing something, they’re just shiny toys.”

‘I get energized’

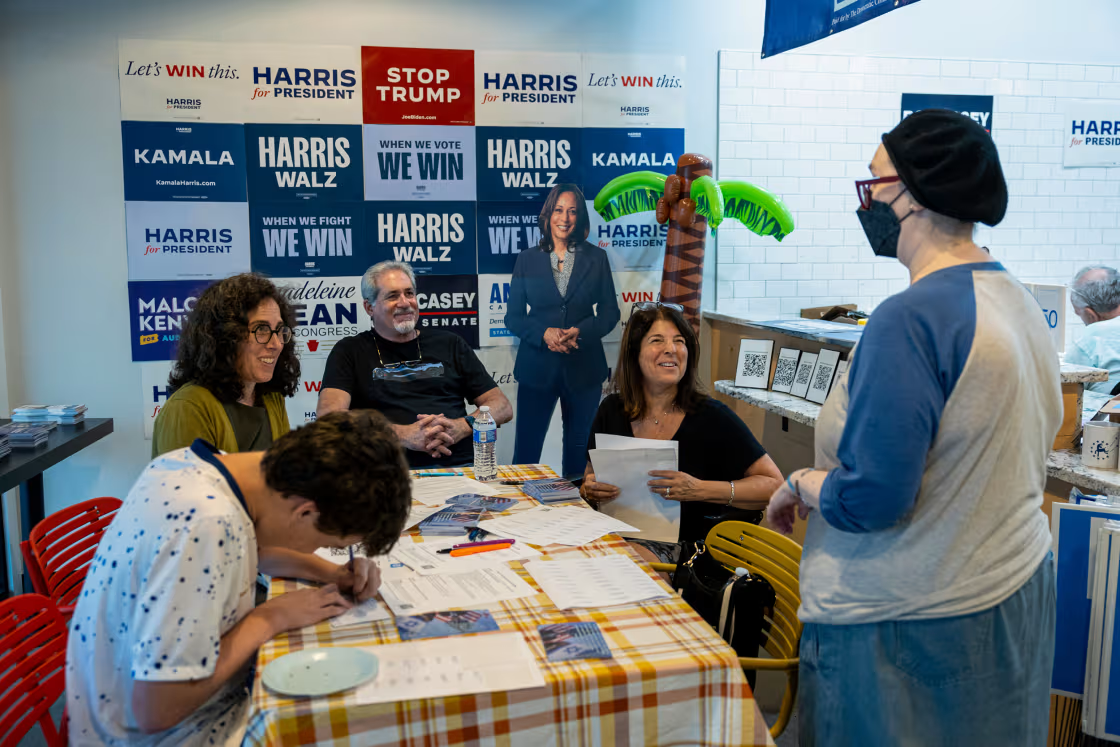

A nerve center of the Harris ground game is its office in Wayne. On a recent afternoon, volunteers came in for training and to gather materials needed to meet voters and record responses on a cellphone app.

A camaraderie pervaded the room as supporters sat at desks filled with Harris campaign literature. The walls were plastered with campaign signs and wallboards with handwritten numbers showing the latest door-knocking goals.

Though hopeful about Pennsylvania, the volunteers also confided that they’re deeply nervous about the outcome on Nov. 5.

Showing up at the office and working among like-minded people pursuing a common goal is one antidote to the anxiety, said Susan Clark, a retired lawyer now living in Oslo, Norway, who left her home to join the Harris volunteer team for the final month of the campaign.

“I wake up in the morning and I read The New York Times and The Philadelphia Inquirer and I think, ‘Oh, my God!’” she said. “And then I come here and I get energized and think we can do it!”

This story first appeared on NBCNews.com. More from NBC News: